Treatments for patients with laryngeal cancer often have an impact on physical, social, and psychological functions.

ObjectiveTo evaluate quality of life and voice in patients treated for advanced laryngeal cancer through surgery or exclusive chemoradiation.

MethodsRetrospective cohort study with 30 patients free from disease: ten total laryngectomy patients without production of esophageal speech (ES); ten total laryngectomy patients with tracheoesophageal speech (TES), and ten with laryngeal speech. Quality of life was measured by SF-36, Voice-Related Quality of Life (V-RQOL), and Voice Handicap Index (VHI) protocols, applied on the same day.

ResultsThe SF-36 showed that patients who received exclusive chemoradiotherapy had better quality of life than the TES and ES groups. The V-RQOL showed that the voice-related quality of life was lower in the ES group. In the VHI, the ES group showed higher scores for overall, emotional, functional, and organic VHI.

DiscussionQuality of life and voice in patients treated with chemoradiotherapy was better than in patients treated surgically.

ConclusionThe type of medical treatment used in patients with laryngeal cancer can bring changes in quality of life and voice.

Tratamentos para pacientes com câncer de laringe podem ter grande impacto na função física, social e psicológica.

ObjetivoAvaliar qualidade de vida e voz de pacientes tratados de câncer avançado de laringe por meio cirúrgico ou quimioradioterapia exclusiva.

MétodosEstudo coorte retrospectivo com 30 pacientes livres da doença: sendo 10 laringectomizados totais sem produção de voz esofágica (SVE); 10 laringectomizados totais com voz traqueoesofágica (VTE) e 10 com voz laríngea. A qualidade de vida foi mensurada pelos protocolos SF-36; Qualidade de Vida em Voz (QVV) e Índice de Desvantagem Vocal (IDV), aplicados no mesmo dia.

ResultadosNo SF-36, observou-se que pacientes que receberam quimioradioterapia exclusiva apresentam melhor qualidade de vida do que o grupo de VTE e SVE. No QVV observou-se que a qualidade de vida relacionada à voz é menor no grupo SVE. No IDV grupo, SVE apresentou escore maior para IDV total, emocional, funcional e orgânica.

DiscussãoQualidade de vida e voz dos pacientes tratados com quimioradioterapia é melhor do que os pacientes tratados cirurgicamente.

ConclusãoO tipo de tratamento médico utilizado em pacientes com câncer de laringe pode trazer alterações na qualidade de vida e voz.

The World Health Organization defines quality of life as complete physical, social, and mental well-being, and not just absence of disease.1 The voice, as a major vehicle of communication, plays a key role in the quality of life of patients, and should be considered as an indicator of health or disease.2

Treatments for patients with laryngeal cancer can have a major impact on physical, social, and psychological function, thus altering their quality of life.3 To know the impact that treatment can have on quality of life of patients with laryngeal cancer is of utmost importance for clinicians and researchers who aim not only to cure their patients, but also to achieve their complete well-being.

Laryngeal cancer is one of the most common types to affect the upper airways.4 It represents 25% of malignant tumors of the head and neck, and affects mainly men.5 Although survival is the main interest concerning the patient's treatment, other parameters such as quality of life, speech, voice function, and complications of treatment are important when therapies are compared, such as surgery and chemoradiation.6

Two types of treatment are used when patients are diagnosed with advanced laryngeal cancer: exclusive chemoradiation or total laryngectomy. When the selected option is total laryngectomy, the patient's voice is completely lost, with consequent problems in communication and personal interactions.6

Communication is an essential part of social life.7 Although it appears that patients with laryngeal preservation have better quality of life, the toxic effects of chemoradiation and scarring after treatments can lead to hoarseness, dysphagia, or pain, which can affect quality of life.8

Both chemoradiation and total laryngectomy affect quality of life, although in different ways.9 For patients who undergo total laryngectomy as treatment modality, there are three possibilities for vocal rehabilitation: esophageal speech (ES), tracheoesophageal speech (TES), and electronic larynx. The first two are the most often used.10 Patients who were rehabilitated with tracheoesophageal prosthesis have a significantly higher speech pattern when compared to patients who used other methods of communication.11 Total laryngectomy brings functional limitations to the individual, and these do not necessarily translate into poorer quality of life. In a survey conducted in 2010, the authors observed significant changes in speech and deglutition functions in patients treated for laryngeal cancer.5

Several questionnaires have been developed to assess the health and quality of life of patients with chronic diseases, and may be used in patients with laryngeal cancer. These questionnaires have been used in previous studies,7,12–16 such as: SF-36 – this is a multidimensional questionnaire consisting of 36 items, comprehending eight scales: functional capacity (FC) related to restrictions to daily activities; physical aspect (PA), regarding the influence of physical limitations in daily activities or work; pain (P), related to pain and its influence on daily life; general health status (GHS), which estimates the general health and self-expectations about the future development of health; vitality (V), related to the feeling of being full of energy or exhausted; social aspects (SA), related to the influence of physical or mental limitations in social activities; emotional aspects (EA), assessing the influence of emotional problems in daily activities or work; and mental health (MH), on the general mental health status, including anxiety, depression, and mood. It has a final score ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 corresponds to the worst general health status and 100 to the best health status. This questionnaire has been translated and validated for Brazilian Portuguese.17

Voice-related Quality of Life (V-RQOL) – the V-RQOL has been translated and validated for Brazilian Portuguese.18 This questionnaire contains ten questions covering two domains: social–emotional and physical functioning. The score for each question ranges from 1 to 5, where 1 represents “not a problem” and 5 “a very big problem.” The calculation of the final score is made based on the rules employed in several questionnaires on quality of life. A standard score is calculated from the raw score, and a higher value indicates that the quality of life aspects are not impaired by the voice functionality. The maximum score is 100 (best quality of life), and the minimum score is 0 (worst quality of life), both for a particular domain, and for the overall score.

IDV – a protocol that evaluates the Voice Handicap Index (VHI), translated and validated for Brazilian Portuguese as IDV.19 It consists of 30 items that assesses three areas: functional, organic, and emotional, with ten items each, aimed to the concept of disadvantage. The scores are calculated using simple summation, and may vary from 10 to 120; the higher the value, the greater the voice handicap. Scores from 0 to 30 are considered low, indicating that there is a probable alteration associated with voice inadequacy; 31–60, moderate change in vocal inadequacy; 61–120, a significantly severe deterioration of a voice problem.

Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate quality of life and voice of patients treated for advanced laryngeal cancer, and to correlate it with the treatment modalities used for these patients.

Materials and methodsParticipantsThis study was submitted and approved under number 528/2011 by the institution's Research Ethics Committee. Patient recruitment was conducted through the Hospital Cancer Registry. The data collection was performed from January of 2000 to January of 2008. During this period, 257 patients were diagnosed with laryngeal cancer. The inclusion criteria were: patients with tumor stage T3 and T4; patients treated for laryngeal cancer; with no associated neurological alterations; patients without evidence of disease for at least four years.

Patients with metastases, tumor recurrence, tumor stage T1 and T2, presence of residual disease, tracheostomy, or requiring feeding through a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube were excluded from the study. Of the 257 patients with laryngeal tumors, only 153 (59.53%) had tumor stage T3 and T4. Of the total sample of T3 and T4 stages, only 73 (47.71%) were alive at the time of the study. Patients included in the study were contacted by telephone in January of 2012.

Of the 73 patients invited, only 36 (49.31%) agreed to participate. In order to have groups with the same number of patients, the first 30 patients who answered the call were enrolled. Of these, 28 (80%) were men and two (20%) were women, aged between 45 and 85 years (mean 65 years). Patients were grouped by type of treatment: the first group (G1) consisted of ten patients submitted to total laryngectomy (six with radiotherapy and four without radiotherapy) and who communicated by writing or gestures; the second group (G2) consisted of ten patients submitted to total laryngectomy (five with radiotherapy and five without radiotherapy) and who used tracheoesophageal prosthesis; the third group (G3) consisted of ten patients who were treated with exclusive chemoradiation and had preserved larynx.

The procedures performed were: application of the SF-36 protocol to measure quality of life of individuals; application of the VR-QOL to verify the quality of life and voice; application of the VHI to assess the voice handicap index; and also vocal self-evaluation and auditory perception analysis of individuals’ general level of the vocal quality.

The SF-36, VR-QOL, and VHI protocols were applied on the same day in all participating subjects. Questionnaire applications and voice analyses were performed by four speech therapists specialized in vocal rehabilitation of patients with head and neck malignancies. Data interpretation was performed by a team comprising two of the speech therapists and two otorhinolaryngologists specialized in head and neck surgery.

For vocal self-assessment, subjects were instructed to assess what they thought of their own voice, through a three-point scale: (1) good; (2) moderate; and (3) poor. At the auditory perception analysis (APA), the individuals had their voices recorded in a laptop (Samsung Intel® Atom™ CPUN455@1.66Hz 1.67GHz), using the software SoundForge® (Sony Creative Software Inc.), release 4.5. Recordings were performed with a headset microphone (Bright®) positioned at a fixed distance of five centimeters from the mouth, in an acoustically treated room. The following samples were collected: sustained “A” vowel and counting numbers from 1 to 10, at the usual frequency and intensity.

The auditory perception analysis was performed by four speech therapists, who were aware that the study population consisted of individuals treated for advanced laryngeal cancer, but were unaware of the treatment option used, as the voices were recorded and they did not have eye contact with patients. The speech therapists were instructed to classify voices through a three-point scale by selecting one of the following alternatives: (1) good; (2) moderate; and (3) poor. The voices were recorded and then played through speakers in an acoustically treated room.

The chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test (for expected values <5) were used to compare categorical variables between the three groups, whereas the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare numerical variables between the three groups, due to the absence of normal distribution of variables. Concordance analysis of the assessment of patients’ voices between speech therapists was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The Wilcoxon's test for related samples was used to compare the assessment of the speech therapists and patient's self-evaluation.

The significance level for statistical tests was set at 5% (p<0.05).

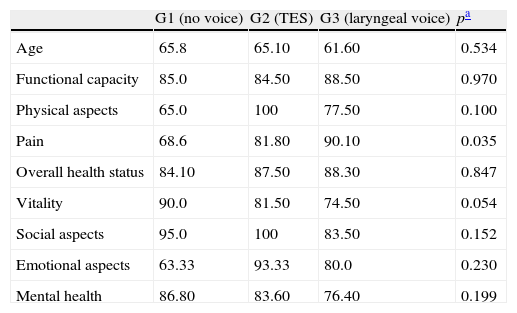

ResultsThe overall quality of life of patients was assessed using the SF-36. In Table 1, it was observed that all groups presented changes in quality of life, but the only items with significant differences were pain and vitality. G1 complained more often of pain than G3, which had a score closer to 100. Regarding vitality, G3 complained of having less vitality.

Comparison of the items of the SF-36 questionnaire according to study group.

| G1 (no voice) | G2 (TES) | G3 (laryngeal voice) | pa | |

| Age | 65.8 | 65.10 | 61.60 | 0.534 |

| Functional capacity | 85.0 | 84.50 | 88.50 | 0.970 |

| Physical aspects | 65.0 | 100 | 77.50 | 0.100 |

| Pain | 68.6 | 81.80 | 90.10 | 0.035 |

| Overall health status | 84.10 | 87.50 | 88.30 | 0.847 |

| Vitality | 90.0 | 81.50 | 74.50 | 0.054 |

| Social aspects | 95.0 | 100 | 83.50 | 0.152 |

| Emotional aspects | 63.33 | 93.33 | 80.0 | 0.230 |

| Mental health | 86.80 | 83.60 | 76.40 | 0.199 |

SF-36 questionnaire on quality of life, where a score closer to 100 indicates better quality of life and score closer to zero, poorer quality of life; No voice, patients submitted to total laryngectomy, without voice; TES, patients submitted to total laryngectomy rehabilitated with voice prosthesis, with tracheoesophageal speech.

The results of SF-36 questionnaire demonstrated that patients treated surgically and who communicated through gestures or writing complained more often of pain when compared with patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis or treated exclusively with chemoradiation. It was also demonstrated that patients with total laryngectomy with tracheoesophageal prosthesis and exclusive chemoradiation therapy had better quality of life, but vitality was higher in G1 (Table 1).

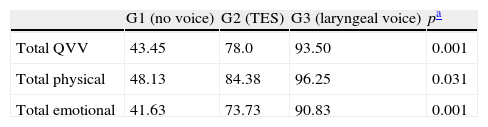

Data on Table 2 demonstrates that patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis had better quality of life scores when compared with G1 (without vocal rehabilitation), but worse than the group with preserved larynx.

Comparative statistical analysis of the QVV questionnaire items according to the study group.

| G1 (no voice) | G2 (TES) | G3 (laryngeal voice) | pa | |

| Total QVV | 43.45 | 78.0 | 93.50 | 0.001 |

| Total physical | 48.13 | 84.38 | 96.25 | 0.031 |

| Total emotional | 41.63 | 73.73 | 90.83 | 0.001 |

QVV, quality of life and voice questionnaire, where scores close to 100 indicate better quality of life and voice; No voice, patients submitted to total laryngectomy, without voice; TES, patients submitted to total laryngectomy, rehabilitated with voice prosthesis, with tracheoesophageal speech.

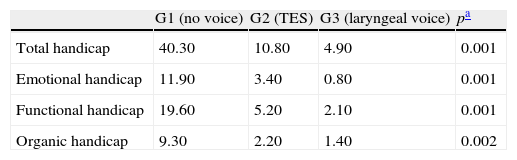

In Table 3, regarding the VHI, it can be observed that the G1 (without voice) had a higher score in all items, showing that patients with no voice perceive themselves as having a major vocal disadvantage compared to the other groups, while patients with laryngeal voice had the lowest scores in all items.

Comparative statistical analysis of the VHI questionnaire items according to the study group.

| G1 (no voice) | G2 (TES) | G3 (laryngeal voice) | pa | |

| Total handicap | 40.30 | 10.80 | 4.90 | 0.001 |

| Emotional handicap | 11.90 | 3.40 | 0.80 | 0.001 |

| Functional handicap | 19.60 | 5.20 | 2.10 | 0.001 |

| Organic handicap | 9.30 | 2.20 | 1.40 | 0.002 |

VHI, voice handicap index, where scores closer to 100 indicate greater perception of voice handicap; no voice, patients submitted to total laryngectomy, without voice; TES, patients submitted to total laryngectomy, rehabilitated with voice prosthesis, with tracheoesophageal speech.

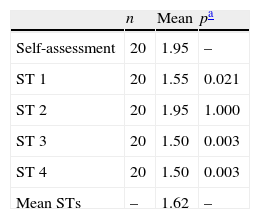

Table 4 presents the comparative analysis of the evaluation of speech therapists and patient self-assessment. There was a significant difference between the self-assessment of the patient and that made by speech therapists 1, 3, and 4, whose mean assessments were lower than patients’ self-assessment. There was no significant correlation between the evaluations of the four speech therapists (ICC=0.108; 95% CI: −0.066 to 0.373; p=0.127). There was no significant agreement between examiners.

Comparative statistical analysis between speech therapists and patient.

| n | Mean | pa | |

| Self-assessment | 20 | 1.95 | – |

| ST 1 | 20 | 1.55 | 0.021 |

| ST 2 | 20 | 1.95 | 1.000 |

| ST 3 | 20 | 1.50 | 0.003 |

| ST 4 | 20 | 1.50 | 0.003 |

| Mean STs | – | 1.62 | – |

ST, speech therapist.

The mean assessment by STs 1, 3, and 4 was lower than patients’ self-assessment (1.95).

Patients treated with exclusive chemoradiation therapy presented similar results to patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis at the self-assessment (p=1.000).

DiscussionIt is difficult to assess quality of life and voice of patients treated for advanced laryngeal cancer, assessing the medical, psychological, and social impact on the life of each patient is difficult, but it is essential in order to establish parameters of rehabilitation and support.5

The SF-36 is one of the most popular tools to assess quality of life in cancer patients, due to its high specificity and reliability.17

The results of the present study support previous findings that the quality of life of patients after total laryngectomy for laryngeal cancer submitted to vocal rehabilitation with tracheoesophageal prosthesis may be similar to the quality of life of patients who received chemoradiation therapy, despite the different qualities of voice. In these patients, not only the treatment choice is relevant for a good quality of life, but also the method of voice rehabilitation after surgery.6 Thus, it was observed that quality of life of patients with tracheoesophageal voice was closer to the quality of life of patients who received exclusive chemoradiation therapy, whereas patients submitted to total laryngectomy without vocal rehabilitation had worse quality of life. This finding is corroborated by the study of Clements et al., which observed a worse quality of life in total laryngectomized patients who communicated through gestures.3 Successful speech rehabilitation with tracheoesophageal prosthesis after total laryngectomy can be as effective as treatment with chemoradiation therapy for laryngeal cancer, regarding psychosocial reintegration and functional ability.20

Therefore, as demonstrated in the study by Giordano et al., patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis had better quality of life when compared with G1 (without vocal rehabilitation), but worse when compared with the group with preserved larynx.

In agreement with the study by Schuster et al., it was observed that patients with tracheoesophageal speech appreciated their new method of communication, but not as much as patients with a preserved larynx.7 Terrell et al. also reported that patients who underwent exclusive chemoradiation tended to have better quality of life, with better scores at the SF-36, when compared with patients who underwent total laryngectomy.8

When the patients’ self-assessment is compared with the evaluation made by speech therapists, it can be observed that speech therapists found the voice of patients with tracheoesophageal speech (Table 4) to be the worst, perhaps due to a more critical sense regarding voice quality, as the self-assessment of patients in both groups was similar. These findings are different from those in the study by Finizia et al., which found a significant difference in the self-assessment of patients, where total laryngectomized patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis evaluated their voices as being worse than patients with preserved larynx.4

Regarding quality of life and voice, the results indicate that not only the method of treatment used is important (total laryngectomy vs. chemoradiation), as well as the presence of vocal rehabilitation after total laryngectomy, as there was a significant difference between G1 and G2. Although patients in both G2 and G3 had a functioning voice, there was no significant difference in vocal quality. G2, whose patients use a tracheoesophageal prosthesis as a method of communication, has worse voice-related quality of life when compared to patients from G3, who had the larynx preserved, showing that the natural larynx is irreplaceable.

This finding differs from those by Finizia et al., who reported that the quality of life of patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis was better than that of patients who received radiotherapy alone, but it is similar to the results of the studies by Oridate et al. and by Boscolo-Rizzo et al.6,21,22 In the study by Terrel et al., all patients submitted to total laryngectomy had, in the long-term, considerable time to readjust to their new condition, and therefore their scores could be higher, as they were less worried about difficulties with volume, clarity, and overall ability to speak.8 It is believed that this is due to the fact that patients submitted to total laryngectomy, as they lived for some time without voice, lost their auditory memory; when they have the opportunity of communication, the acquired voice is perceived by them as excellent.

Patients who received exclusive chemoradiation therapy, as they are aware of their pretreatment voices, classify their post-treatment voices as moderate when compared to the pre-treatment. Studies demonstrate that patients who underwent total laryngectomy are more concerned with the physical consequences of surgery and interference in social activities than with impaired communication.23 In the immediate postoperative period, patients already show functional limitations. However, subsequently, when the fear of death and the uncertainty of cure have been overcome, individuals begin to observe and assess the functional limitations resulting from their treatment by assigning positive and negative points that will directly influence their quality of life.

According to Gomes and Rodrigues et al., total laryngectomized patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis have better quality of life as, unlike patients with exclusive chemoradiation therapy, they undergo speech therapy; this close contact with the therapist can bring a positive influence to the patient's vocal perception.5 Robertson reported that patients on chemoradiation therapy often do not undergo speech and deglutition therapy, and that this can impair their quality of life, when compared with total laryngectomized patients.24

When comparing the self-assessment of patients treated solely with chemoradiotherapy, with total laryngectomy and tracheoesophageal prosthesis, the present study observed a different result that by Finizia et al.,6 who reported that the vocal quality of chemoradiation therapy is better assessed by patients than total laryngectomized patients. Another important quality of life factor is the aspect of being disease-free, as its presence influences the quality of life due to physical, social, and psychological negative impacts that treatment failure brings to the patient. If a group of total laryngectomized patients without voice, with voice, and preserved larynx, but with persistent had been assessed, perhaps their quality of life would be worse than in the three groups without the disease. Therefore, the cure of the disease itself must also be considered in the quality of life assessment.

ConclusionRegarding quality of life and voice of the patients treated for advanced laryngeal cancer and currently disease-free, it can be concluded that:

- 1.

Among those submitted to total laryngectomy, patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis have better quality of life and voice.

- 2.

Vocal self-assessment is similar among patients undergoing chemoradiation therapy and patients with tracheoesophageal prosthesis. However, in the audiological assessment, the tracheoesophageal voice has the worst performance.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rossi VC, Fernandes FL, Ferreira MA, Bento LR, Pereira PS, Chone CT. Larynx cancer: quality of life and voice after treatment. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;80:403–8.

Institution: Discipline of Speech Therapy and Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck; Faculdade de Ciências Médicas (FCM) Hospital das Clínicas (HC) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, SP, Brazil.