Angiofibromas are the most frequently encountered histologically benign but potentially locally destructive vascular tumors that generally originate from the posterior lateral wall of the nasopharynx. These neoplasms are typically found in adolescent males and rarely seen after 25 years of age.1 Angiofibromas located in extranasopharyngeal sites are uncommon, and sporadically reported in the literature. In this article, we present a very rare case, the fourth case in the literature, of an angiofibroma arising from the middle turbinate in a 13 year-old male who presented with recurrent epistaxis and nasal blockage.2–4 The clinical presentation, endoscopic examination, radiological findings, histopathologic evaluation and management of this pathology are discussed.

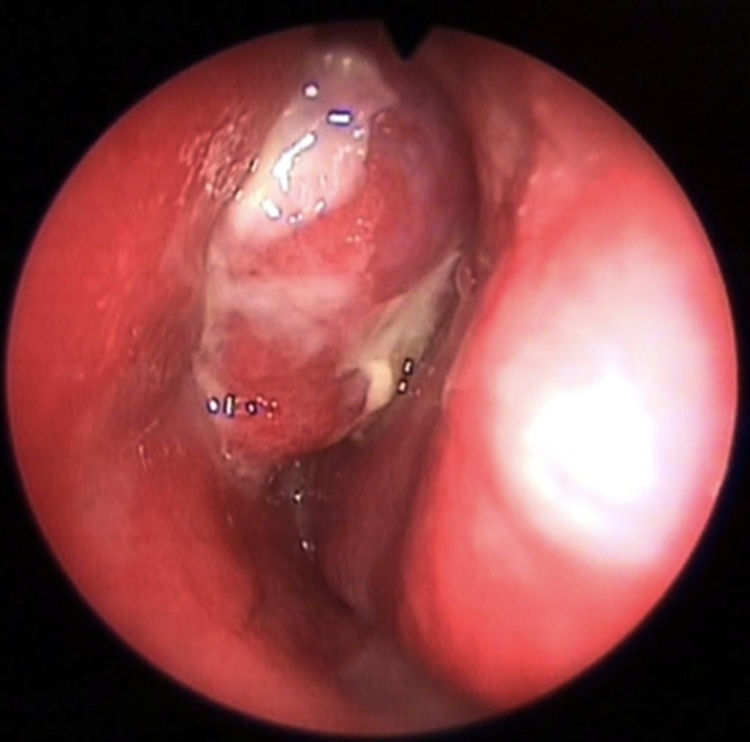

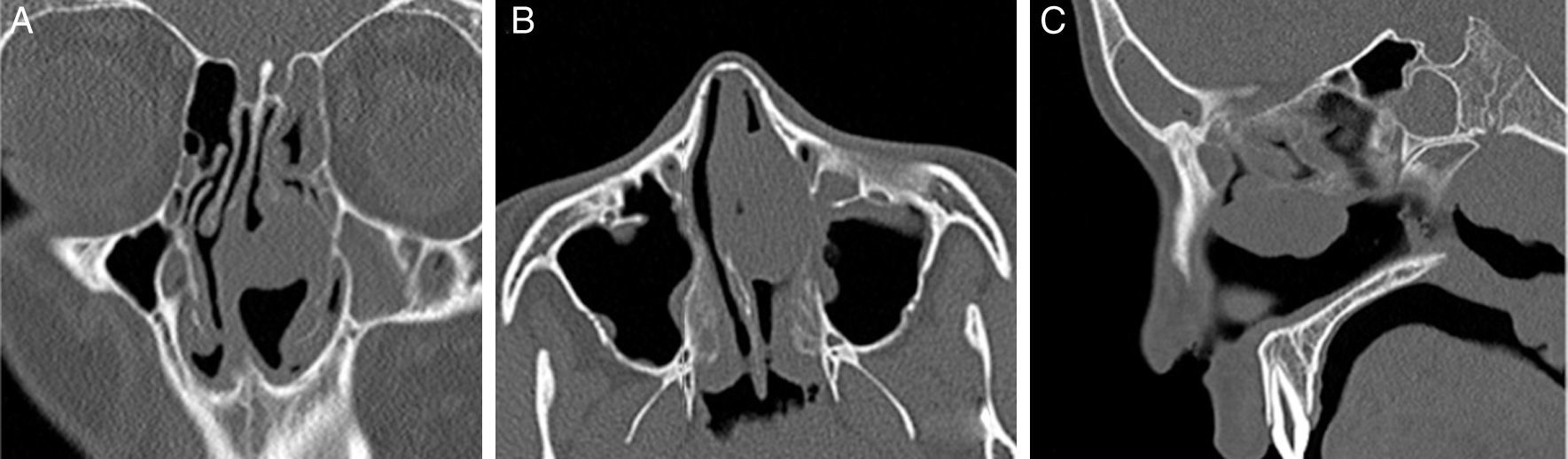

Case reportA 13 year-old nonsmoker male patient came to our clinic with recurrent epistaxis and nasal blockage complaints. He had experienced these symptoms for 3 months. He had no history of notable nasal trauma, nasal surgery, allergy, infection or systemic disease. He had been treated several times with different local and systemic medications without success. On endoscopic examination (Fig. 1), a polypoid mass arising from the anteroinferior part of the left middle turbinate was detected. The routine non contrast-enhanced paranasal computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 2A–C) showed a soft tissue opacity that filled the anterior part of the left nasal cavity. There was no sign of sinus invasion or bony destruction. Based on the location and size of the tumor, our judgment was that the mass could be completely removed endoscopically to perform histopathological evaluation for definitive diagnosis without any other preoperative investigation such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), angiography or embolization.

The polypoid mass was completely removed with endoscopic subtotal middle turbinectomy under general anesthesia. The tumor was lobular, red-grayish, about 30mm in length, and 10mm in diameter (Fig. 3). There were no serious bleeding intra or post-operatively. After removal, the material underwent histopathological examination. After 24h, the patient was discharged without any complication. Oral antibiotic was prescribed for seven days.

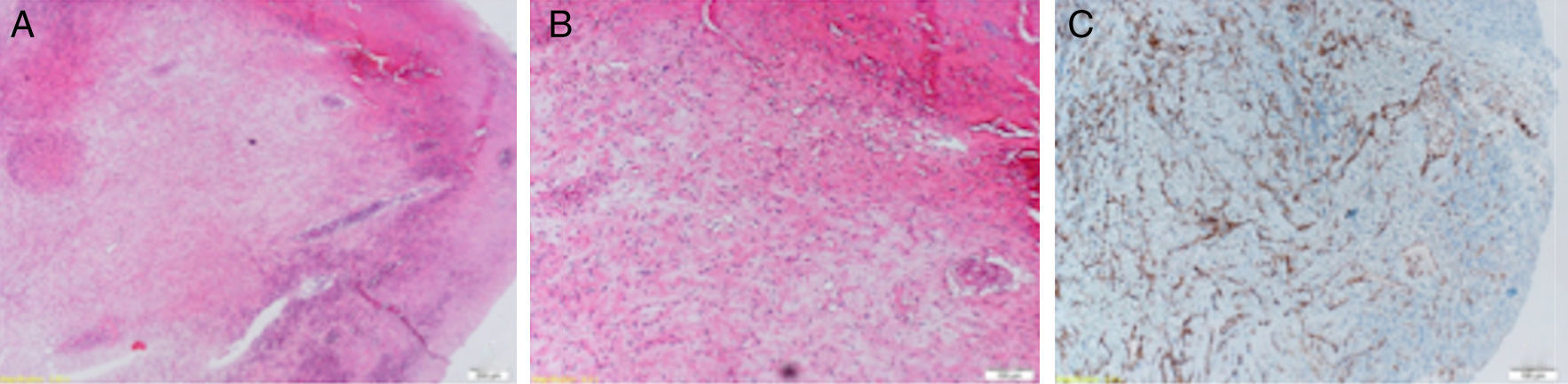

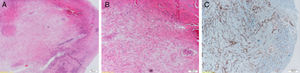

The tissue was fixed in 10% formaldehyde, routinely processed and fixed in paraffin for microscopic examination. Consecutive sections, with 4μm in thickness, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The exam revealed metaplastic squamous epithelium with respiratory epithelium remnants on the tumor surface. Under the epithelium, many irregular vascular structures ranging from capillaries and sinusoids to large bleeding areas, wrinkled with one layer of flat endothelial cells lying in a fibrous stroma that composed of spindle cells were found. The tumor consisted of numerous blood vessels of various sizes and shapes surrounded by a fibrous stroma. Immunohistochemical methods using CD34 antibody staining, showed vascular structures more clearly (Fig. 4A–C). From these features, histopathological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of angiofibroma. The endoscopic control evaluation of one-month post-surgery showed a completely recovered left nasal cavity, with no sign of recurrence.

DiscussionMany theories have been described to clarify the etiopathogenesis of angiofibromas, including developmental, hormonal, and genetic but none of them have been generally accepted. According to Tillaux, these tumors may originate in the tissue of the anterior part of the atlas at the inferior region of the sphenoid bone.5 Brunner called this tissue “fascia basalis” as he found no cartilage in it.6 Consequently, an angiofibroma of the middle turbinate is extremely unusual, and our case is the fourth reported case in the PubMed and Google Search literature.2–4

Primary extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas have rarely been reported. Unlike the classic juvenile angiofibromas, extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas are more frequently seen in an older age group and more commonly in females. Our case in a 13 year old male is very unusual according to the medical literature knowledge. Primary extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas most commonly originate from the nasal septum, followed by inferior and middle turbinates. The most common symptoms of nasopharyngeal angiofibromas are unilateral nasal blockage, epistaxis, and facial pain. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma symptoms depend on their localization.3 Our patient came to our clinic with complaints of recurrent epistaxis and nasal blockage.

The management of angiofibromas includes endoscopic nasal examination, preoperative radiologic evaluation and histopathologic examination.7 CT, MRI, and arteriography are valuable diagnostic methods in the evaluation of angiofibromas. Common indications for non-contrast enhanced CT include extremity soft tissue swelling, nasal polyp, infection, or trauma, but contrast is necessary if vascular involvement or injury are suspected.8 CT easily shows the bony structure if a surgical procedure is contemplated, however MRI helps distinguishing tumors from chronic infections and shows intracranial extension, and can be employed as a method for patients’ follow-up. Moreover; an angio-MRI provides valuable information about vascular supply avoiding the need of a diagnostic angiography. Selective arteriography determines the vascular pattern and blood flow, and if needed, it also allows a selective preoperative embolization.8,9 In the present case, the tumor was located in the anterior-inferior part of the middle turbinate as confirmed by endoscopic examination and preoperative non-contrast enhanced paranasal CT. We initially suspected that it were a polyp of the middle turbinate and decided for total resection followed by histopathologic examination. In many patients with turbinate tumors, the location and extent of the disease allow the surgeon to completely remove the tumors with an endoscopic nasal surgery. The result of the histopathologic examination revealed an unexpected middle turbinate angiofibroma.

Many different therapeutic options have been used to treat angiofibromas including surgery, hormonal therapy, radiation, and chemotherapy. Surgery, however, remains the main option of treatment.3 In some cases, preoperative angioembolization can be performed to reduce the intraoperative bleeding. In our case we completely excised the tumor performing a subtotal middle turbinectomy, without serious bleeding. We did not carry out preoperative angioembolization because of both, the risks of the procedure, and the easily resectable location of the tumor.

The recurrence rate for nasopharyngeal angiofibromas is about 25% for the first surgery and 40% for the second surgery.10 The recurrence rate of middle turbinate angiofibromas seems to be lower but only a few cases have been reported; this fact is probably associated to an acceptable surgical exposure and the possibility of resection of the entire tumor body. In our case, endoscopic nasal examination at the 18th month postoperative follow-up visit was completely normal.

The differential diagnosis of middle turbinate angiofibroma includes fibrosed antrochoanal or nasoethmoidal polyp and other fibrovascular tumors, such as juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas, capillary hemangioma, hemangiopericytoma, and solitary fibrous tumor.3

ConclusionMiddle turbinate angiofibromas are extremely rare tumors. Their exact cause is not known, but they possibly originate from an ectopic tissue. Endoscopic examination, radiological evaluation and histopathological analysis are required for correct diagnosis. Total surgical resection of the tumor is the main modality of treatment.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Toplu Y, Can S, Sanlı M, Sahin N, Kizilay A. Middle turbinate angiofibroma: an unusual location for juvenile angiofibroma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;84:122–5.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial.