There is a strong association between vertigo and migraine. Vestibular migraine (VM) was described in 1999, and diagnostic criteria were proposed in 2001 and revised in 2012.

ObjectiveTo compare the diagnostic criteria for VM proposed in 2001 with 2012 criteria with respect to their diagnostic power and therapeutic effect of VM prophylaxis.

MethodsClinical chart review of patients attended to in a VM clinic.

ResultsThe 2012 criteria made the diagnosis more specific, restricting the diagnosis of VM to a smaller number of patients, such that 87.7% of patients met 2001 criteria and 77.8% met 2012 criteria. Prophylaxis for VM was effective both for patients diagnosed by either set of criteria and for those who did not meet any of the criteria.

ConclusionsThe 2012 diagnostic criteria for VM limited the diagnosis of the disease to a smaller number of patients, mainly because of the type, intensity, and duration of dizziness. Patients diagnosed with migraine and associated dizziness demonstrated improvement after prophylactic treatment of VM, even when they did not meet diagnostic criteria.

Há forte associação entre vertigem e enxaqueca. A migrânea vestibular (MV) foi descrita em 1999 e critérios diagnósticos foram propostos em 2001 e revisados em 2012.

ObjetivoComparar os critérios diagnósticos para MV propostos em 2001 com os de 2012, através de seu poder diagnóstico e efeito terapêutico da profilaxia da MV.

MétodoRevisão de prontuários de pacientes atendidos em uma clínica de MV.

ResultadosOs critérios de 2012 tornaram o diagnóstico mais específico, restringindo a MV a um número menor de pacientes, sendo que 87,7% dos pacientes preencheram os critérios de 2001 e 77,8% preencheram os critérios de 2012. O tratamento profilático para MV foi eficaz tanto para pacientes diagnosticados por algum dos critérios quanto para aqueles que não se enquadravam em qualquer critério.

ConclusõesOs critérios diagnósticos de 2012 para MV restringiram o diagnóstico da doença para um menor número de pacientes, principalmente por causa do tipo de tontura, a sua intensidade e duração. Pacientes com enxaqueca diagnosticada e tontura associada apresentaram melhora após o tratamento profilático da MV mesmo quando não preenchem critérios diagnósticos.

Dizziness is one of the most common complaints in medical practice, especially in the geriatric age group, with an incidence of up to 30% per year.1 Despite the clinical presentation, which often manifests itself vaguely, and the fact that many doctors still feel insecure in the management of patients with dizziness, it is possible to reach an accurate diagnosis in most cases.2

Vestibular disorders are the most prevalent causes of dizziness. Among them, the most common are, in descending order, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), endolymphatic hydrops, and vestibular migraine (VM). This latter condition represents more than 11% of the causes of vestibular diseases, present in about 1% of the general population.2,3

Migraine is a multifactorial chronic disease, common in genetically susceptible individuals,4 and characterized by a throbbing unilateral headache associated with photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting.5 VM can be a disabling illness that affects about 18% of women and 6% of men,5 coursing with otoneurological symptoms such as vertigo, hearing loss, tinnitus, and aural fullness; during a crisis, many patients exhibit these symptoms in the absence of headache.5

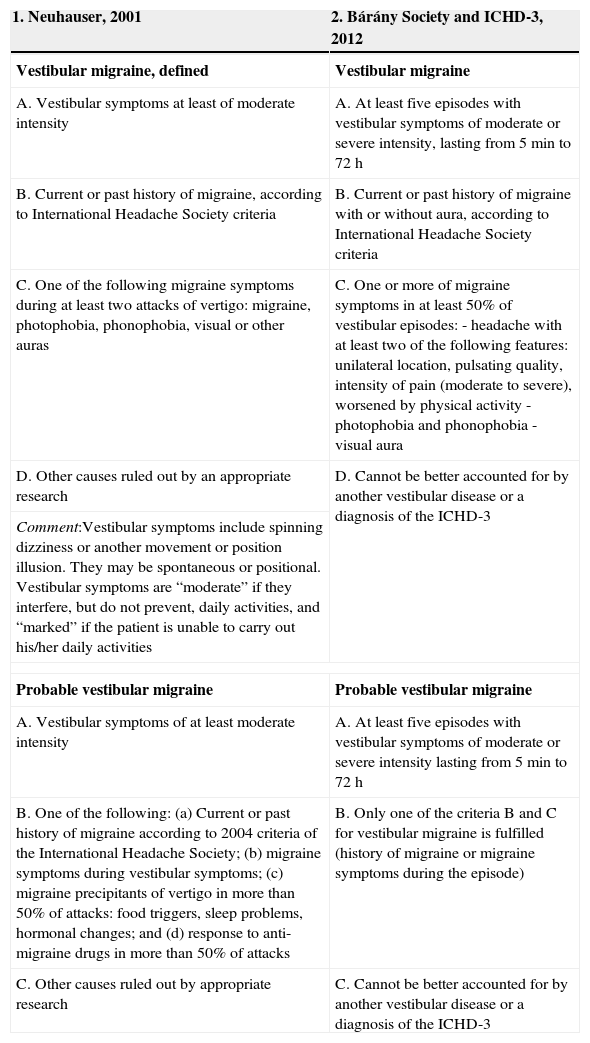

The association between migraine and dizziness has been known for a long time and occurs three times more often than if it was caused only by chance.6 VM as a particular entity, however, was only recently described (in 1999) by Dieterich and Brandt,7 characterized by vertigo and migraine attacks. To date, its definition is not uniform among authors. Diagnostic criteria (Table 1) were proposed by Neuhauser in 20018 and revised in 2012 by the Bárány Society and the International Headache Society (IHD),3 and were included in the third version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3).9

| 1. Neuhauser, 2001 | 2. Bárány Society and ICHD-3, 2012 |

|---|---|

| Vestibular migraine, defined | Vestibular migraine |

| A. Vestibular symptoms at least of moderate intensity | A. At least five episodes with vestibular symptoms of moderate or severe intensity, lasting from 5min to 72h |

| B. Current or past history of migraine, according to International Headache Society criteria | B. Current or past history of migraine with or without aura, according to International Headache Society criteria |

| C. One of the following migraine symptoms during at least two attacks of vertigo: migraine, photophobia, phonophobia, visual or other auras | C. One or more of migraine symptoms in at least 50% of vestibular episodes:- headache with at least two of the following features: unilateral location, pulsating quality, intensity of pain (moderate to severe), worsened by physical activity- photophobia and phonophobia- visual aura |

| D. Other causes ruled out by an appropriate research | D. Cannot be better accounted for by another vestibular disease or a diagnosis of the ICHD-3 |

| Comment:Vestibular symptoms include spinning dizziness or another movement or position illusion. They may be spontaneous or positional. Vestibular symptoms are “moderate” if they interfere, but do not prevent, daily activities, and “marked” if the patient is unable to carry out his/her daily activities | |

| Probable vestibular migraine | Probable vestibular migraine |

| A. Vestibular symptoms of at least moderate intensity | A. At least five episodes with vestibular symptoms of moderate or severe intensity lasting from 5min to 72h |

| B. One of the following: (a) Current or past history of migraine according to 2004 criteria of the International Headache Society; (b) migraine symptoms during vestibular symptoms; (c) migraine precipitants of vertigo in more than 50% of attacks: food triggers, sleep problems, hormonal changes; and (d) response to anti-migraine drugs in more than 50% of attacks | B. Only one of the criteria B and C for vestibular migraine is fulfilled (history of migraine or migraine symptoms during the episode) |

| C. Other causes ruled out by appropriate research | C. Cannot be better accounted for by another vestibular disease or a diagnosis of the ICHD-3 |

The treatment of VM involves two situations10:

- 1.

Crisis of migraine-associated vertigo: for the treatment of dizziness spells, recommended drugs are the same used for other acute attacks of vertigo: meclizine or dimenhydrinate, for example.

- 2.

Intercrisis period: prophylactic drugs are used. The indication for prophylaxis is the intensity or frequency of symptoms, or even the patient's will. To date, drugs used for this purpose are the same used for non-dizziness migraine prophylaxis: beta-blockers, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants. The choice of drug is based on the patient's profile: hypertensive patients can use beta-blockers; anxious and depressive patients can use antidepressants, especially tricyclic depressants and venlafaxine; patients without comorbidities may receive anticonvulsants, especially topiramate and sodium valproate.

The aim of this study was to compare the diagnostic criteria for VM proposed by Neuhauser in 2001 against the criteria reviewed by the Bárány Society and the International Headache Society in 2012, with an evaluation of the diagnostic power and the therapeutic effect of VM prophylaxis in patients seen at Vestibular Migraine Outpatient Clinic, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP).

MethodsA cross-sectional historical cohort study was conducted. The authors evaluated clinical records of all patients attended to at the VM outpatient clinic (Discipline of Otology and Neurotology, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, UNIFESP) since its inception from 2011 until June 2013. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UNIFESP, under code 19615313.13.5.0000.5505.

All clinical records of patients with VM were included, and the following information was taken into account:

- •

Epidemiological data: name, gender, age, profession, and place of birth;

- •

Clinical features of the disease;

- •

Past medical history;

- •

Results of treatments evaluated by a visual analogue scale (VAS).

The medical records of patients with other disorders causing dizziness and/or headache and those with illegible records or with incomplete or divergent information were excluded.

The information obtained allowed for classification of patients according to the diagnostic criteria proposed in 2001 and 2012. According to these criteria, patients were classified as having definitive or probable VM.

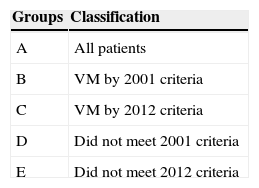

Patients were classified into subgroups to assess their improvement in symptoms (Table 2). A VAS was used for headache and dizziness. Each patient was evaluated by VAS in the pre-prophylaxis period and again by VAS after prophylactic treatment with different drugs. The estimated treatment time ranged from three to six months. Clinical improvement was determined by the difference between these scores, termed “gain.”

The results were statistically analyzed, and Student's t and ANOVA tests were performed for quantitative variables. The significance level of 5% was adopted; therefore, values of p≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsNinety-four clinical records from the VM outpatient clinic were analyzed, of which 81 were eligible. Thirteen clinical records without the information sought or presenting inconsistencies were excluded. Of the 81 patients, 76 (93.8%) were female. The average age was 46 years.

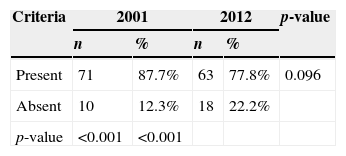

Among the 81 patients, 67 (82.7%) fully met the diagnostic criteria proposed in 2001 for definitive VM and four (4.9%) for probable VM. Thus, 71 of the 81 patients (87.7%) met one of the two criteria (Table 3). The other ten patients had migraine (according to ICHD-3 criteria)3 and vestibular symptoms, but did not meet the diagnostic criteria for VM, even after ruling out other causes of dizziness.

Regarding 2012 criteria, 60 (74.1%) were classified as definitive VM, and three (3.1%) as probable VM. Thus, 63 of the 81 patients (77.8%) met criteria for VM (Table 3).

Of those ten patients who did not meet 2001 diagnostic criteria, four (40%) had non-vertigo dizziness (i.e. with no illusion of movement or position), and eight (80%) had mild dizziness.

Of those 18 patients who did not meet 2012 diagnostic criteria, four patients (22%) had non-vertigo dizziness, eight patients (44%) had mild dizziness, and 13 (72%) had symptoms of dizziness only for a few seconds. All ten patients who did not meet 2001 diagnostic criteria also could not receive a diagnosis of VM according to current criteria (2012).

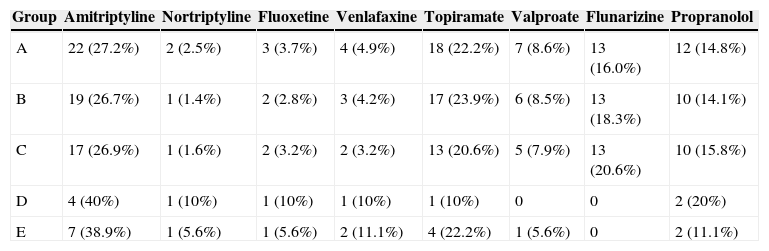

The treatment given included antidepressants, anticonvulsants, calcium channel inhibitors, and β-blockers (Table 4). The medication was chosen considering the patient's profile, as recommended in the literature.

Distribution of drugs used for vestibular migraine prophylaxis according to the group.

| Group | Amitriptyline | Nortriptyline | Fluoxetine | Venlafaxine | Topiramate | Valproate | Flunarizine | Propranolol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 22 (27.2%) | 2 (2.5%) | 3 (3.7%) | 4 (4.9%) | 18 (22.2%) | 7 (8.6%) | 13 (16.0%) | 12 (14.8%) |

| B | 19 (26.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (2.8%) | 3 (4.2%) | 17 (23.9%) | 6 (8.5%) | 13 (18.3%) | 10 (14.1%) |

| C | 17 (26.9%) | 1 (1.6%) | 2 (3.2%) | 2 (3.2%) | 13 (20.6%) | 5 (7.9%) | 13 (20.6%) | 10 (15.8%) |

| D | 4 (40%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (20%) |

| E | 7 (38.9%) | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | 2 (11.1%) | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 2 (11.1%) |

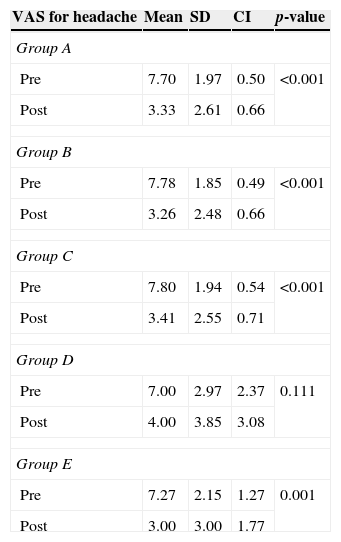

VAS scores for pre-treatment headache ranged from 2 to 10, with a mean of 7 to 7.8 between groups. Conversely, VAS scores for headache after prophylactic treatment ranged from 0 to 9, with a mean of 3 to 4 between groups (Table 5).

Mean scores of the visual analogue scale for headache by subgroup of patients.

| VAS for headache | Mean | SD | CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | ||||

| Pre | 7.70 | 1.97 | 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Post | 3.33 | 2.61 | 0.66 | |

| Group B | ||||

| Pre | 7.78 | 1.85 | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Post | 3.26 | 2.48 | 0.66 | |

| Group C | ||||

| Pre | 7.80 | 1.94 | 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Post | 3.41 | 2.55 | 0.71 | |

| Group D | ||||

| Pre | 7.00 | 2.97 | 2.37 | 0.111 |

| Post | 4.00 | 3.85 | 3.08 | |

| Group E | ||||

| Pre | 7.27 | 2.15 | 1.27 | 0.001 |

| Post | 3.00 | 3.00 | 1.77 | |

SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; Group A, all patients; Group B, patients who met one of the 2001 criteria for vestibular migraine; Group C, patients who met one of the 2012 criteria vestibular migraine; Group D, patients who did not meet any of old criteria; Group E, patients who did not meet any of the new criteria.

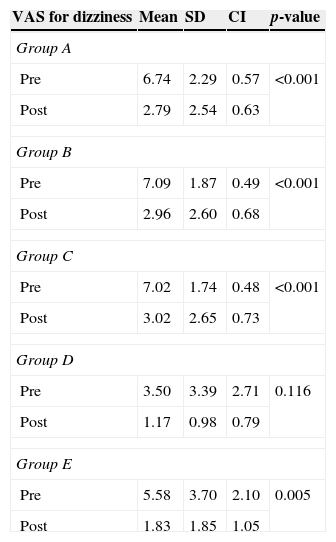

VAS scores for pretreatment dizziness ranged from 0 to 10, with a mean of 3.5 to 7.09 between groups. VAS scores for dizziness after prophylactic treatment ranged from 0 to 8, with a mean of 1.17 to 3.02 between groups (Table 6).

Mean scores of the visual analogue scale for dizziness by subgroup of patients.

| VAS for dizziness | Mean | SD | CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | ||||

| Pre | 6.74 | 2.29 | 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Post | 2.79 | 2.54 | 0.63 | |

| Group B | ||||

| Pre | 7.09 | 1.87 | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Post | 2.96 | 2.60 | 0.68 | |

| Group C | ||||

| Pre | 7.02 | 1.74 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Post | 3.02 | 2.65 | 0.73 | |

| Group D | ||||

| Pre | 3.50 | 3.39 | 2.71 | 0.116 |

| Post | 1.17 | 0.98 | 0.79 | |

| Group E | ||||

| Pre | 5.58 | 3.70 | 2.10 | 0.005 |

| Post | 1.83 | 1.85 | 1.05 | |

SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; Group A, all patients; Group B, patients who met one of the 2001 criteria for vestibular migraine; Group C, patients who met one of the 2012 criteria vestibular migraine; Group D, patients who did not meet any of old criteria; Group E, patients who did not meet any of the new criteria.

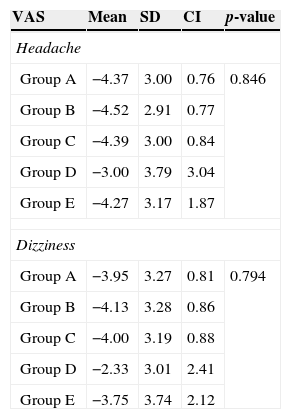

For headache, the mean values of gain ranged from −3.00 to −4.52. For dizziness, the mean values of gain ranged from −2.33 to −4.13. When compared between groups, in neither case did gain values for headaches and for dizziness demonstrate a statistically significant difference (Table 7).

Mean of gain for visual analogue scale scores for headache and dizziness by subgroups of patients.

| VAS | Mean | SD | CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | ||||

| Group A | −4.37 | 3.00 | 0.76 | 0.846 |

| Group B | −4.52 | 2.91 | 0.77 | |

| Group C | −4.39 | 3.00 | 0.84 | |

| Group D | −3.00 | 3.79 | 3.04 | |

| Group E | −4.27 | 3.17 | 1.87 | |

| Dizziness | ||||

| Group A | −3.95 | 3.27 | 0.81 | 0.794 |

| Group B | −4.13 | 3.28 | 0.86 | |

| Group C | −4.00 | 3.19 | 0.88 | |

| Group D | −2.33 | 3.01 | 2.41 | |

| Group E | −3.75 | 3.74 | 2.12 | |

SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; Group A, all patients; Group B, patients who met one of the 2001 criteria for vestibular migraine; Group C, patients who met one of the 2012 criteria vestibular migraine; Group D, patients who did not meet any of old criteria; Group E, patients who did not meet any of the new criteria.

VM is a heterogeneous condition, usually episodic and with varying symptoms; however, this disease can be chronic, as can migraine without dizziness.11 This is a prevalent condition in women in the third and fourth decades of life4; this was also observed in the results of this study.

This study found a decrease in the number of patients diagnosed with VM according to the criteria proposed in 2012, in comparison with those of 2001. The diagnostic criteria of 2012 were proposed by the Bárány Society in conjunction with the International Headache Society. Regarding this publication, it can be observed that the principal controversy occurred with respect to the sensitivity and specificity of the criteria, considering that very specific criteria would increase the number of false-negative cases; however, very sensitive criteria would increase the number of false-positive cases.3 Considering this sample, it was clear that the new criteria are more specific, because they restrict the diagnosis to a smaller number of patients.

The type of dizziness and its duration and intensity were the main culprits for this reduction in the number of patients with a diagnosis of VM by the new criteria. The diagnostic criteria of 2012 restricted these characteristics; with their application in this series, eight of 71 patients (11.3%) were excluded. This has resulted in a more specific, but less sensitive, diagnosis.

Although diagnosed with migraine by ICHD-3 criteria, ten patients (12%) did not fit the classification of VM either by 2001 or 2012 criteria. Thus, these patients would no longer receive an etiologic diagnosis. In fact, they would be diagnosed with a vestibular syndrome to be clarified. Nevertheless, these patients were not excluded from this clinic, because of other diagnostic tips, for example, a strong family history of migraine or a history of motion sickness; and, in addition, they showed a good therapeutic response.

Patients diagnosed with VM by the 2001, but not by 2012 criteria, responded to drug therapy in a similar manner to patients in groups B and C, with a statistically significant improvement seen in the VAS scale. This indicates the possibility that these patients are actually suffering VM, and therefore would be considered as false-negative cases by 2012 diagnostic criteria.

The use of diagnostic criteria for the determination of diseases has great scientific value, because this strategy standardizes diagnostics, mainly for scientific studies. However, their value to medical practice should be put in perspective, as there are other, often variables in the art of establishing a diagnosis that are not quantifiable. In the present sample, the results of the prophylactic treatment of patients assessed by VAS showed no statistically significant difference between post-treatment scores of patients who met vs. those who did not meet the diagnostic criteria. There are two possible explanations for this finding: the diagnosis of VM was correct – even in cases that did not fit the diagnostic criteria; or the prophylactic treatment of VM improved the cases of vestibular disorders not resulting from migraine. However, no literature reports of anti-vertigo effect for antidepressant or anticonvulsant drugs could be found. Additional studies are needed so that a more thorough understanding of this problem is obtained.

ConclusionsThe 2012 diagnostic criteria for VM restrict the diagnosis of this disease to a lesser number of patients. The key features responsible for this reduction were the type of dizziness, and its intensity and duration.

Patients diagnosed with migraine and with complaints of an associated dizziness showed improvement of dizziness (by VAS), after drug prophylaxis for VM.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Salmito MC, Morganti LOG, Nakao BH, Simões JC, Duarte JA, Ganança FF. Vestibular migraine: comparative analysis between diagnostic criteria. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:485–90.