Malignant tumors of the temporal bone are rare, with an estimated incidence of about 0.8–1.0 per 1,000,000 inhabitants per year. The vast majority of these tumors are squamous cell carcinomas and their treatment is eminently surgical.

ObjectiveThis study is an attempt at systematizing the forms of clinical presentation, the therapeutic possibilities, and oncological outcomes of patients with malignant tumors of the temporal bone in a tertiary hospital in Portugal.

MethodsThe authors present a retrospective study of temporal bone tumors treated and followed during otorhinolaryngology consultations between 2004 and 2014. A review of the literature is also included.

ResultsOf the 18 patients included in the study, 16 had a primary tumor of the temporal bone, in most cases with squamous cell carcinoma histology. Of these, 13 patients were treated with curative intent that always included the surgical approach. Disease persistence was observed in one patient and local recurrence in five patients, on average 36.8 months after the initial treatment.

ConclusionsThe anatomical complexity of the temporal bone and the close associations with vital structures make it difficult to perform tumor resection with margins of safety and thus, tumor relapses are almost always local. A high level of suspicion is crucial for early diagnosis, and stringent and prolonged follow-up after treatment is essential for diagnosis and timely treatment of recurrances.

Os tumores malignos do osso temporal são raros, com uma incidência estimada de cerca de 0,8–1 por milhão de habitantes por ano. A grande maioria são carcinomas espino-celulares e o seu tratamento é eminentemente cirúrgico.

ObjetivoEste trabalho tem como objetivo tentar sistematizar as formas de apresentação clínica, as possibilidades terapêuticas e os resultados oncológicos de doentes com tumores malignos do osso temporal num hospital terciário em Portugal.

MétodoOs autores apresentam um estudo retrospectivo de tumores do osso temporal tratados e acompanhados em consultas de otorrinolaringologia entre 2004 e 2014. É também apresentada uma revisão da literatura.

ResultadosDos 18 doentes incluídos no estudo, 16 apresentavam um tumor primário do osso temporal, na maioria dos casos com histologia de carcinoma espinocelular. Destes, 13 doentes foram submetidos a tratamento com intuito curativo que incluiu sempre uma abordagem cirúrgica. Verificou-se persistência da doença em 1 doente e recidiva local em 5 doentes, em média 36,8 meses após o tratamento inicial.

ConclusõesA complexidade anatómica do osso temporal e as estreitas relações com estruturas de importância vital tornam difícil a exérese tumoral com margens de segurança, pelo que as recidivas tumorais são quase sempre locais. Um nível de suspeição elevado é fundamental para um diagnóstico precoce e o seguimento rigoroso e prolongado após o tratamento é essencial para o diagnóstico e tratamento oportuno das recidivas.

Tumors of the temporal bone include skin cancer of the pinna extending to the temporal bone, primary tumors of the external auditory canal (EAC), of the middle ear, of the mastoid or petrous apex, and metastatic lesions in the temporal bone. Primary malignant tumors of the temporal bone have an estimated incidence of 0.8–1.0 per 1,000,000 inhabitants per year, and 60–80% of them are squamous cells carcinomas.1

Metastatic lesions in the temporal bone are very rare and usually originate from primary breast, lung, or kidney tumors.2 Although they can occur at all ages, temporal bone tumors are more common in the 6th to 7th decade of life and in the male gender.3 A multifactorial etiology has been suggested for these tumors and ionizing radiation is the most important risk factor for tumors originating in the skin of the pinna and EAC, especially in fair-skinned individuals.4

The development of temporal bone carcinomas in patients who have undergone radiotherapy for carcinomas elsewhere in the head has also been described. Lim et al. presented a series of seven patients with a history of radiotherapy for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.5

Although chronic otitis media has been associated with the presence of the temporal bone carcinoma, there is no scientific evidence that this entity is involved in its etiology.6

Agents such as chlorinated disinfectants or human papillomavirus in cases of carcinomas associated with inverted papillomas have been mentioned as possible carcinogens.7–9

Temporal bone tumors manifest with nonspecific symptoms, such as otorrhea, ear pain, or hearing loss, that are often attributed to inflammatory ear diseases. Thus, although they usually have a superficial location, diagnosis is often delayed.10

Tumors of the pinna and the EAC are known to be more aggressive and have a higher risk of recurrence and lymph node metastasis, possibly due to the presence of the fusion of multiple embryonic planes in this region, which may facilitate tumor dissemination.11–13

In addition to a complete otorhinolaryngological examination and the histolopathological analysis, diagnostic imaging assessment of the head and neck are essential for accurate tumor diagnosis and staging. Computerized tomography (CT) with contrast allows assessing the bone erosion and the presence of regional adenopathy, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast allows a better assessment of its extension to the parotid gland, temporomandibular joint, petrous apex, and intracranial invasion. In locally advanced tumors, positron-emission tomography (PET) allows the exclusion of distant metastasis.1

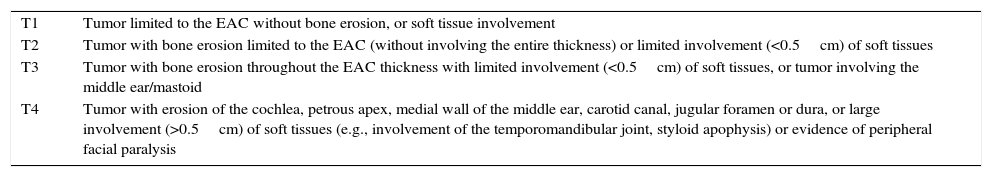

Currently, there is no universally accepted system for the staging of temporal bone carcinomas. The most commonly used is the Pittsburgh modified by Moody et al. in 2000 (Table 1), which is based on physical examination, preoperative CT, and the presence of facial paralysis.14

Modified Pittsburgh staging system for temporal bone carcinomas.

| T1 | Tumor limited to the EAC without bone erosion, or soft tissue involvement |

| T2 | Tumor with bone erosion limited to the EAC (without involving the entire thickness) or limited involvement (<0.5cm) of soft tissues |

| T3 | Tumor with bone erosion throughout the EAC thickness with limited involvement (<0.5cm) of soft tissues, or tumor involving the middle ear/mastoid |

| T4 | Tumor with erosion of the cochlea, petrous apex, medial wall of the middle ear, carotid canal, jugular foramen or dura, or large involvement (>0.5cm) of soft tissues (e.g., involvement of the temporomandibular joint, styloid apophysis) or evidence of peripheral facial paralysis |

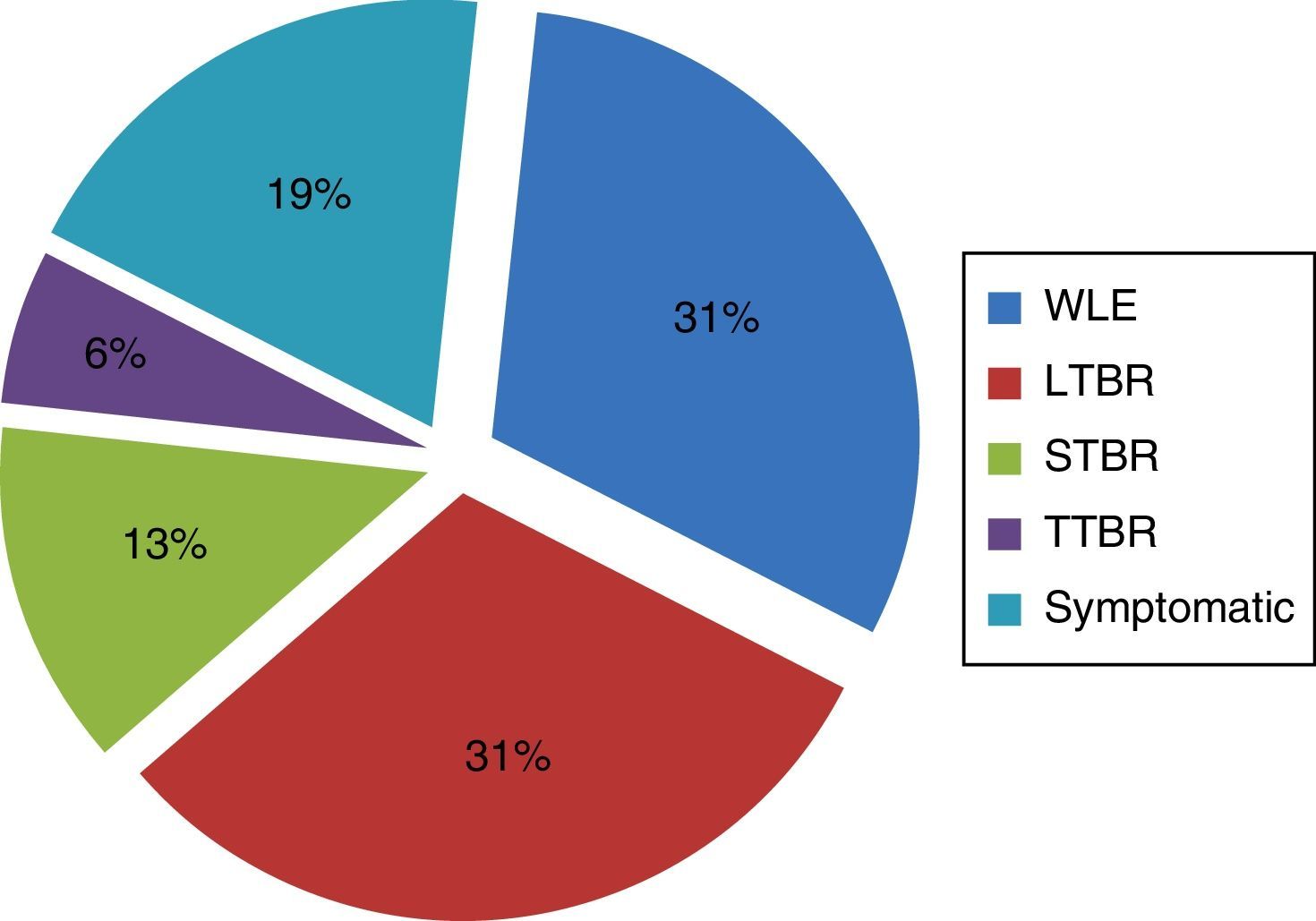

Treatment of temporal bone tumors is a challenge for otorhinolaryngologists due to the presence of significant neurovascular structures in this region. This usually includes the extended tumor surgical resection, which according to its length, can be a wide local excision (WLE), a lateral temporal bone resection (LTBR), a subtotal temporal bone resection (STBR), or total temporal bone resection (TTBR). This surgical approach may be combined with cervical dissection, with a superficial or total parotidectomy and/or supplementary radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, according to the disease extent, presence of lymph node metastases, histological subtype, available resources, and surgeon's preference.11,15,16

MethodsThe authors performed a retrospective longitudinal cohort study covering the period between January of 2004 and August of 2014, which included all patients with a diagnosis of malignant tumor of the temporal bone treated in the Otorhinolaryngology Service of a tertiary hospital in Portugal.

Demographic data, clinical history, histological diagnosis, tumor staging, and treatments performed were recorded. All patients had a minimum of six months of follow-up after treatment.

A literature review was also performed through the PubMed database, regarding tumors of the temporal bone and their treatment.

Results and discussionThe study included 18 patients with malignant tumors of the temporal bone. Of these, 16 had primary malignant tumors of the temporal bone, one patient had a unilateral mastoid metastasis of breast carcinoma, and another patient had Langerhans cell histiocytosis that affected both mastoids. The latter two patients were submitted to mastoidectomy, in the first case for the surgical excision of the secondary lesion and, in the second case, to confirm the diagnosis. Only the data of patients with primary temporal bone tumors were considered for the analysis shown herein.

Of the 16 patients with primary malignant tumors of the temporal bone, 56.25% were men and 43.75% women, and the mean age at diagnosis was 58.7 years. Most patients had squamous cell carcinomas (68.75%), and the remainder had basal cell carcinomas (25%) and one adenoid cystic carcinoma (6.25%). 81.25% of the tumors originated from the EAC and the remaining involved the pinna (12.5%) and the middle ear (6.25%).

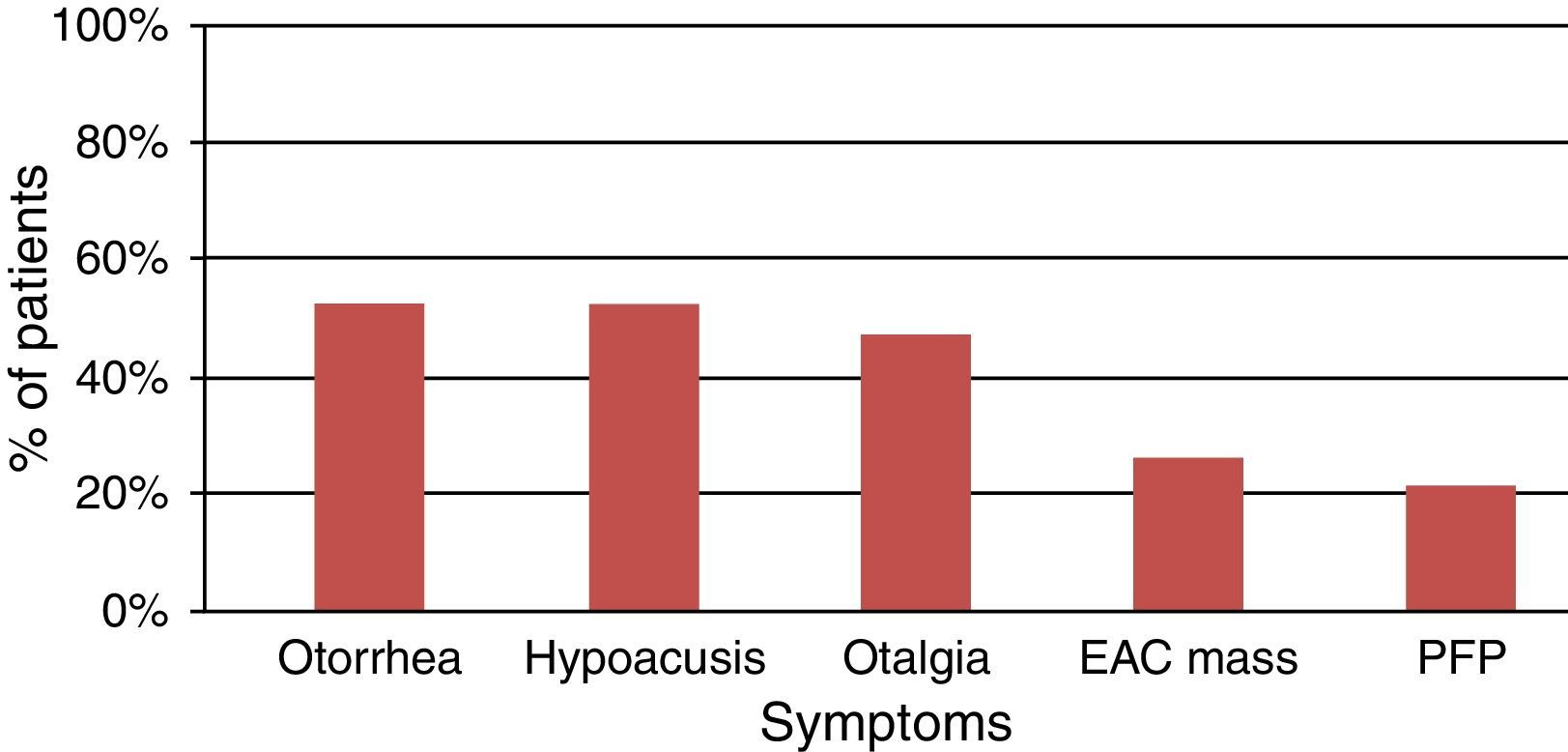

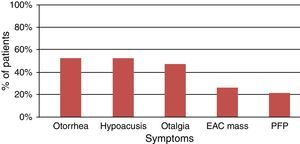

The most common symptoms reported by patients were otorrhea, hypoacusis, and otalgia (Fig. 1), which is in accordance with that described in the literature. Symptoms such as trismus and peripheral facial nerve paralysis are rare and indicative of advanced-stage disease. Symptom duration has been associated with patient survival, so it is very important to confirm the diagnosis when symptoms do not improve with standard treatment suitable for a benign disease, such as external otitis.17,18 The treatment of these patients should include a detailed examination of the external ear and skin of the pre-auricular region, the EAC, tympanic membrane, parotid gland, cervical ganglia, and cranial nerves.

At the time of diagnosis, 37.5% of the tumors were staged as T1, 18.75% as T2, and 43.75% as T4, in accordance with the Modified Pittsburgh System. Metastatic lymph node disease was identified in only one of the patients at presentation, who had a locally advanced tumor. The estimated incidence of metastases in cervical lymph nodes is 10–23%,4 usually involving levels I and II, and imaging studies are considered to be sufficient for the diagnosis and surgical planning.19

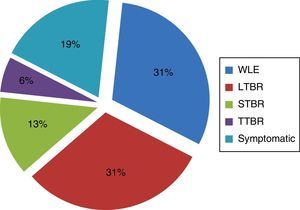

Regarding the performed treatment, symptomatic treatment was performed in 18.75% of patients, due to of the extent of the primary tumor and involvement of important neurovascular structures. In carcinomas of the external ear that did not extend medially beyond the bony-cartilaginous junction in the EAC (31.25%), it was possible to carry out a WLE. However, in most cases (50%) temporal bone resection was required (Fig. 2).

The temporal bone resection was associated with a superficial parotidectomy in 18.75% of patients and in 6.25%, with a total parotidectomy. Only one patient underwent ipsilateral cervical lymph node resection, and the clinical pathology analysis showed no lymph node metastasis.

The main surgical complications were associated with STBR and TTBR. Of the patients submitted to STBR, complete deafness and permanent facial paralysis were observed in two patients. TTBR was performed with preservation of the internal carotid artery and no significant intraoperative complications. The patient has complete deafness, ipsilateral peripheral facial palsy, and persistent dysfunction of the contralateral temporomandibular joint as sequelae.

Adjunctive treatment was carried out in half of the patients, with 37.5% submitted to radiotherapy and 12.5% to both radio- and chemotherapy.

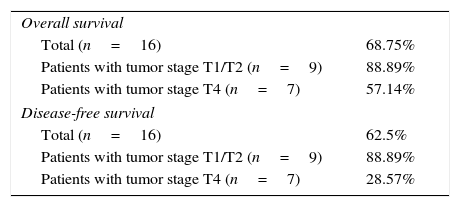

The mean follow-up of patients undergoing surgery was 67 months after the end of treatment and the overall survival was 68.75% (Table 2).

Percentages of overall and disease-free survival.

| Overall survival | |

| Total (n=16) | 68.75% |

| Patients with tumor stage T1/T2 (n=9) | 88.89% |

| Patients with tumor stage T4 (n=7) | 57.14% |

| Disease-free survival | |

| Total (n=16) | 62.5% |

| Patients with tumor stage T1/T2 (n=9) | 88.89% |

| Patients with tumor stage T4 (n=7) | 28.57% |

In patients at early stage of the disease (T1 and T2), there was local recurrence in 44.44%, on average 43 months after treatment. With the exception of a patient that had an adenoid cystic carcinoma who died at 72 months postoperatively, all patients underwent a second surgical excision, and were disease-free after a median follow-up of 66 months.

Regarding cancer patients in advanced stage (T3 and T4), 42.86% underwent symptomatic treatment, one patient had disease persistence after surgery, and 28.57% had local recurrence, on average nine months after the initial treatment. Patients undergoing symptomatic treatment died on average 13 months after the diagnosis.

Of the patients with advanced tumors at admission, 28.57% were disease-free at 58.31 months of follow-up, whereas in patients with tumors at early stage, this percentage was 88.89% (Table 2).

According to the literature and in line with the authors’ experience, treatment with curative intent always includes an en bloc surgical resection, which must be accompanied by total parotidectomy when there is direct involvement of the gland.1 Performing superficial parotidectomy has been advocated when the safety margins are narrow, or if the disease is locally advanced, to assess the presence of intra-parotid lymph node metastases.20,21

Currently, curative surgical treatment is contraindicated if there is involvement of the cavernous sinus, massive intracranial extension, unresectable cervical disease, distant metastasis, or poor general status.17 In situations of dural or brain involvement, the curative surgical treatment can be considered if it is possible to perform an en bloc resection with disease-free margins.1,12

Complementary radiotherapy treatment, such as that performed in the present patients, is indicated in locally advanced tumors (T3–T4) or in the presence of aggressive pathological features, such as the perineural invasion, margins <5mm, or positive margins or lymph node metastasis.20 Regarding the treatment with chemotherapy, there is some evidence that it may be effective in T4 tumors with postsurgical residual or metastatic disease, but it is contra-indicated in other situations.1

Regarding cervical treatment, some authors recommend elective ipsilateral lymph node dissection in locally advanced tumors because of the potential presence of micrometastases in clinically negative necks.22,23 However, as observed in the present study, the incidence of regional lymph node metastasis is low and tumor recurrence is almost always local, so the performance of this procedure remains controversial.

It is generally accepted that the prognosis and overall survival vary considerably depending on the stage of the disease, the treatment protocols, and the aggressiveness of the surgical resection.24 Considering the anatomical location of temporal bone tumors, the prognosis is significantly influenced by any direct involvement of nearby structures, with the extent of the primary tumor representing one of the most important prognostic factors.1 The presence of regional lymph node metastases reflects the tumor aggressiveness; it is associated with local recurrence, not regional recurrence.22 Nonetheless, distant metastases, usually in lung, bone, liver, or brain, are associated with a very poor prognosis.1,14

Thus, the early diagnosis is considered of utmost importance, as well as the performance of a wide surgical excision of the primary tumor. This should take into account the possible associated consequences, as it is important to achieve a balance between the radical extent of the surgery and postoperative morbidity.

Given the frequency of local relapses, a regular and careful follow-up must be conducted to treat recurrent disease in a timely manner.

ConclusionsMalignant tumors of the temporal bone are rare and their initial presentation is often identical to that of inflammatory ear diseases. The otorhinolaryngologist must maintain a high level of suspicion when there is no symptomatic improvement after conventional treatment for inflammatory diseases. The importance of achieving an early diagnosis is reinforced by the poor prognosis of tumors presenting at an advanced stage.

The surgery, with or without complementary radiotherapy, constitutes the basis for the treatment of these tumors. Considering the anatomical complexity and the presence of important neurovascular structures in this region, radical surgeries should take the associated morbidities into account.

A stringent follow-up after surgery is also essential for the diagnosis and timely treatment of relapses, which are mostly local.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: da Silva AP, Breda E, Monteiro E. Malignant tumors of the temporal bone – our experience. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:479–83.