Pharyngocutaneous fistula after larynx and hypopharynx cancer surgery can cause several damages. This study's aim was to derive a clinical decision rule to predict pharyngocutaneous fistula development after pharyngolaryngeal cancer surgery.

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted, including all patients performing total laryngectomy/pharyngolaryngectomy (n=171). Association between pertinent variables and pharyngocutaneous fistula development was assessed and a predictive model proposed.

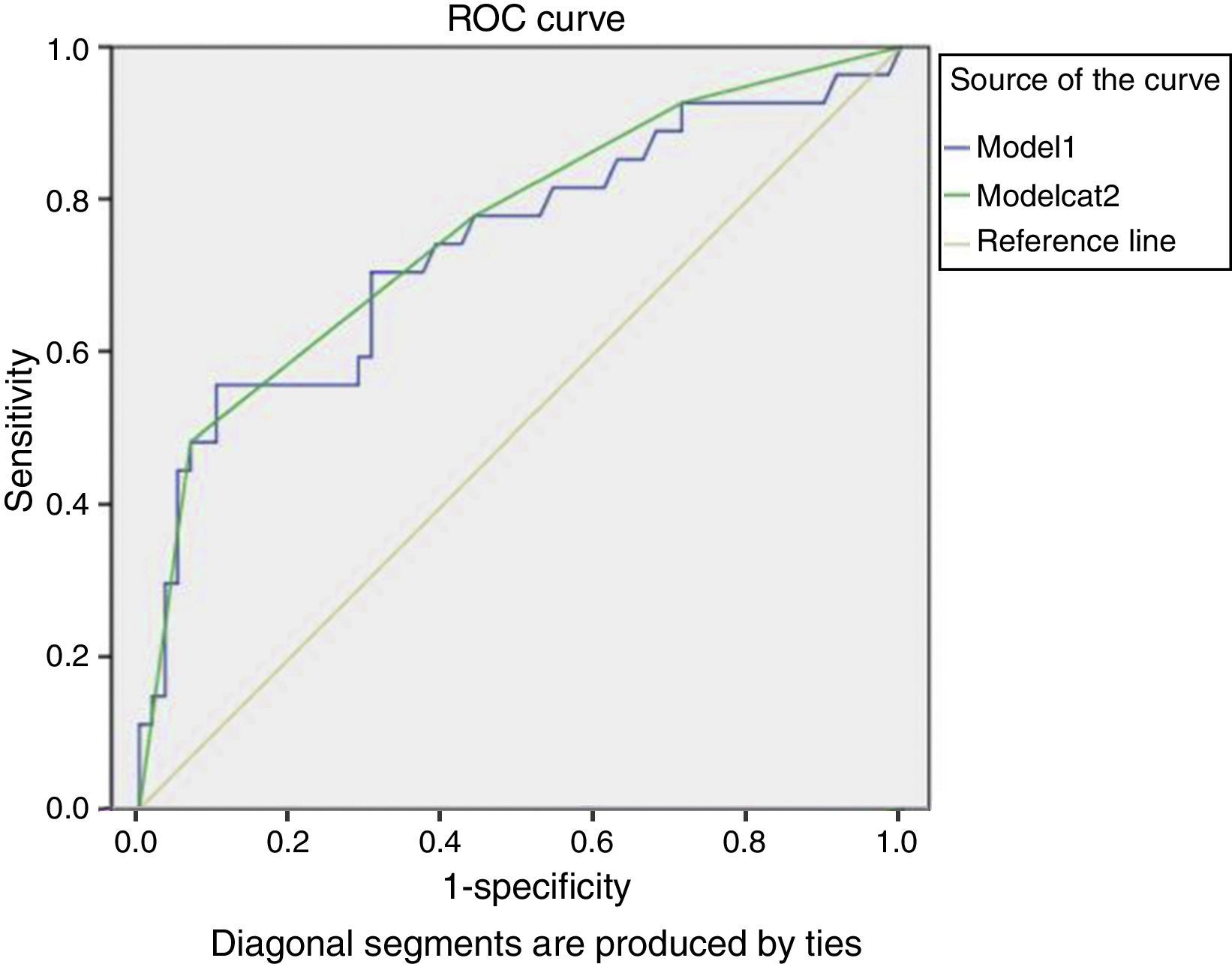

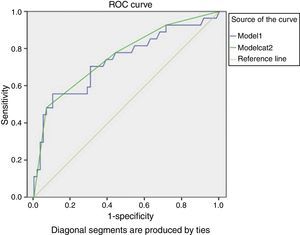

ResultsAmerican Society of Anesthesiologists scale, chemoradiotherapy, and tracheotomy before surgery were associated with fistula in the univariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, only American Society of Anesthesiologists maintained statistical significance. Using logistic regression, a predictive model including the following was derived: American Society of Anesthesiologists, alcohol, chemoradiotherapy, tracheotomy, hemoglobin and albumin pre-surgery, local extension, N-classification, and diabetes mellitus. The model's score area under the curve was 0.76 (95% CI 0.64–0.87). The high-risk group presented specificity of 93%, positive likelihood ratio of 7.10, and positive predictive value of 76%. Including the medium-low, medium-high, and high-risk groups, a sensitivity of 92%, negative likelihood ratio of 0.25, and negative predictive value of 89% were observed.

ConclusionA clinical decision rule was created to identify patients with high risk of pharyngocutaneous fistula development. Prognostic accuracy measures were substantial. Nevertheless, it is essential to conduct larger prospective studies for validation and refinement.

Fístula faringocutânea após cirurgia de câncer de laringe e hipofaringe causa diversos danos. Nosso objetivo foi derivar uma regra de decisão clínica (RDC) para predizer o desenvolvimento da fístula faringocutânea após cirurgia.

MétodoEstudo de coorte retrospectivo incluindo todos os pacientes submetidos à laringectomia total e faringolaringectomia (n=171). Analisou-se a associação entre as variáveis pertinentes e o desenvolvimento da fístula e foi proposto um modelo preditivo.

ResultadosNa análise univariada, a ASA, quimioradioterapia (QRT) e traqueostomia antes da cirurgia foram associadas à fístula. Na análise multivariada, somente a ASA manteve-se estatisticamente significante. Por regressão logística, derivamos um modelo preditivo incluindo: ASA, álcool, QRT, traqueostomia, hemoglobina e albumina pré-operatórias, extensão local, N, DM. A curva ROC do modelo foi 0,76 (95% CI 0,64–0,87). O grupo de alto risco teve especificidade 93%, Likelihood positivo 7,10 e valor preditivo positivo 76%. Incluindo os grupos de médio baixo, médio alto e alto risco, temos sensibilidade de 92%, Likelihood negativo 0,25 e valor preditivo positivo 89%.

ConclusãoCriamos uma RDC para identificar os pacientes de alto risco ao desenvolvimento da fístula faringocutânea. As medidas de acurácia prognóstica foram substanciais. Entretanto, é essencial conduzir estudos prospectivos maiores para validação/refinamento do modelo.

Larynx and hypopharynx cancer represents almost 45% of all treated diseases in this tertiary care hospital's department of otolaryngology, specialized in oncology.

Prevalence of pharyngocutaneous fistula after larynx and pharyngolarynx cancer surgery is reported to be between 9% and 25%.1,2 Its occurrence vastly increases these patients’ length of stay and consequently the treatment cost.3 Moreover, its occurrence can cause, among other physical and psychological damages, the delay in onset of complementary therapies (such as radiotherapy/chemotherapy), consequently delaying recovery.

Until now, no study has proposed a clinical decision rule (CDR) for predicting pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy and primary or rescue pharyngolaryngectomy, with or without neck dissection, and major predictive factors were scarcely assessed.4 Thus, the goal was to derive such a CDR in a sample of patients from this hospital. Its creation is intended to encourage clinical behavior modification in order to avoid development of this complication and thus facilitate the reduction of unnecessary costs as well as improve patients’ quality of life.

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted (longitudinal historical cohort study), consecutively including all the patients performing total laryngectomy/pharyngolaryngectomy, due to cancer of the larynx and hypopharynx, in the Otolaryngology Department of this hospital, from February of 2006 to June of 2011. All patients diagnosed with laryngeal and pharyngolaryngeal cancer were evaluated by the team before final treatment. Only procedures consistent with total laryngectomy with or without partial pharyngectomy and primary closure of the pharyngeal defect were considered in this study. The operations were performed by four different surgeons, two with ten or more years of experience, and two with less.

This study conduction was approved by the Ethics Committee of this hospital.

Data collectionAll variables and outcome occurrence were collected by the principal investigator (SC), between August of 2011 and January of 2012, using the institutional medical records. Follow-up was performed until the patients were discharged.

A systematic review was conducted in order to identify all the predictive risk factors for the pharyngocutaneous fistula development described in the available literature (results not reported in this article).4

All the variables considered as pertinent in this review were collected, namely:

- (a)

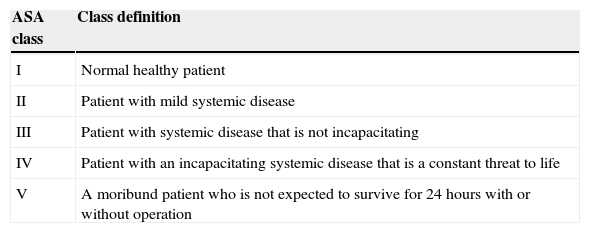

Factors related to the patient: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification (Table 1), alcohol consumption (considered heavy if the patient regularly drank over 1L of alcoholic beverage per day, considered ex-consumers or light consumers if they drank from zero to four cups/day), pre-operative hemoglobin level (<12.4g/dL or ≥12.4g/dL), pre-operative albumin value (<37g/L or ≥37g/L), and presence of major co-morbidities (diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), heart disease, or liver disease).

Table 1.American Society of Anesthesiologists risk classification system.

ASA class Class definition I Normal healthy patient II Patient with mild systemic disease III Patient with systemic disease that is not incapacitating IV Patient with an incapacitating systemic disease that is a constant threat to life V A moribund patient who is not expected to survive for 24 hours with or without operation Source: Amir Qaseem, Vincenza Snow; Nick Fitterman; E. Rodney Hornbake; Valerie A. Lawrence; Gerald W. Smetana; Kevin Weiss, Douglas K. Owens; Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; Risk Assessment for and Strategies To Reduce Perioperative Pulmonary Complications for Patients Undergoing Noncardiothoracic. Surgery: A Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006 Apr;144(8):575–580. - (b)

Factors related to illness: N-classification (based on the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 2010 – 7th edition), surgical intervention performed (total laryngectomy or pharyngolaryngectomy).

- (c)

Factors related to treatment: radiotherapy only (Rt) or chemoradiotherapy (CRT) prior to surgery and tracheotomy prior to operation.

Nutritional deficiency and loss of weight were previously excluded from the analysis because insufficient data were available in the medical records assessed (120 missing).

Regarding outcome, pharyngocutaneous fistula development was confirmed clinically in postoperative daily visits by more than one observer (surgeon and resident) with the utterance content of saliva and the path the fistulous wound analysis.

Statistical analysisAll variables were categorical and their presence in each group (with or without outcome development) was compared using the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, when applicable. Significance was considered as a p-value<0.05.

The inclusion of ten to fifteen subjects per assessed predictive variable is recommended.5 As the present study analyzed the association between 13 variables and an outcome, at least 130 subjects were required.

It is common to observe that, when conducting multivariate analysis, there is a change in several predictive variables’ significance level. Thus, in several studies,5–7 variables have been included in the multivariate analysis when a p-value<0.2 is observed in the univariate analysis. In this manner, it is assured that all pertinent and potentially predictive variables are studied. The same criterion was used for detecting which variables should be included in this study's derived model.

Multivariate analysis, using logistic regression, was conducted for the predictive model's derivation.

After the predictive model was created, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated and, through the “best fit” of the coordinates of the curve, four risk categories were created: high risk (4), medium-high risk (3), medium-low risk (2), and low risk (1). The sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 18.0.

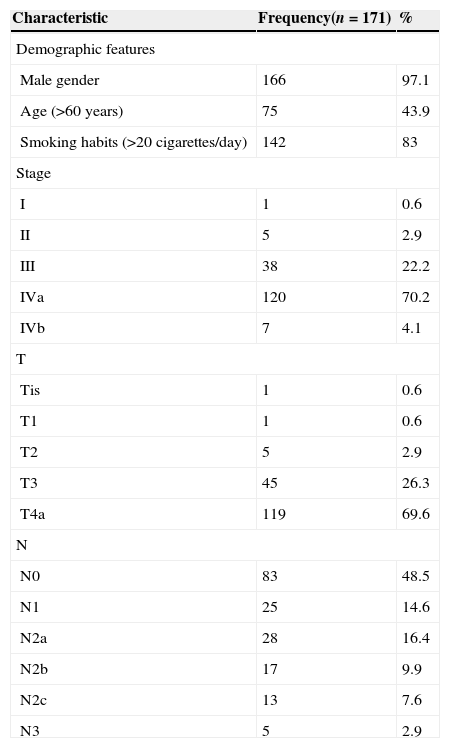

ResultsThis study included 171 subjects, characterized in Table 2.

Characterization of the sample according to TNM stage (AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 2010 – 7th edition) and demographic features.

| Characteristic | Frequency(n=171) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic features | ||

| Male gender | 166 | 97.1 |

| Age (>60 years) | 75 | 43.9 |

| Smoking habits (>20 cigarettes/day) | 142 | 83 |

| Stage | ||

| I | 1 | 0.6 |

| II | 5 | 2.9 |

| III | 38 | 22.2 |

| IVa | 120 | 70.2 |

| IVb | 7 | 4.1 |

| T | ||

| Tis | 1 | 0.6 |

| T1 | 1 | 0.6 |

| T2 | 5 | 2.9 |

| T3 | 45 | 26.3 |

| T4a | 119 | 69.6 |

| N | ||

| N0 | 83 | 48.5 |

| N1 | 25 | 14.6 |

| N2a | 28 | 16.4 |

| N2b | 17 | 9.9 |

| N2c | 13 | 7.6 |

| N3 | 5 | 2.9 |

All the participants were M0 and pharyngeal closure was performed with two layers (muscles and mucosa) of continuous suture or stapler (used whenever possible).

During a mean follow-up of 30 days, 48 subjects (28.1%) developed pharyngocutaneous fistula postoperatively. They were all classified as ASA 2 or 3; 79.2% as high alcohol consumers, almost 48.9% had preoperative hemoglobin level below 12.5g/dL, 16.7% were diabetic patients, 6.2% had some degree of COPD, 22.9% showed impaired liver function or some degree of heart disease, 8.3% had received radiotherapy previously to the operation, 18.8% had undergone chemotherapy/radiotherapy prior to the operation, and in 58.3% an emergency tracheotomy before elective surgery was required. In fact, 45% were performed emergently and 13.3% were elective tracheotomies.

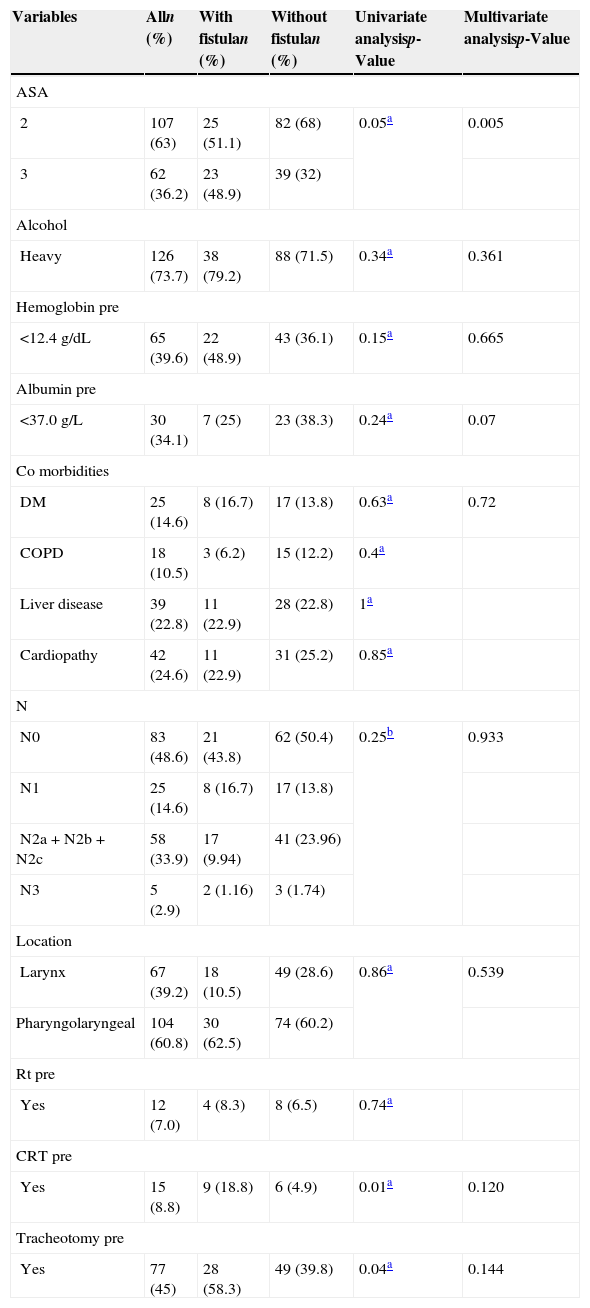

It was observed that patients with advanced stage (IVa and IVb) had the largest absolute number of pharyngocutaneous fistula (n=40) observed in the sample, although it was not statistically significant (p=0.25). However, the 87 remaining patients in these stages (representing almost 50% of the sample) did not develop a fistula. Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed with the inclusion of the relevant factors obtained by a previous systematic review,4 which had potential for inclusion in the predictive model being developed, as already explained (Table 3).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the relationship between the variables included in the clinical decision rule and the frequency of pharyngocutaneous fistula.

| Variables | Alln (%) | With fistulan (%) | Without fistulan (%) | Univariate analysisp-Value | Multivariate analysisp-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA | |||||

| 2 | 107 (63) | 25 (51.1) | 82 (68) | 0.05a | 0.005 |

| 3 | 62 (36.2) | 23 (48.9) | 39 (32) | ||

| Alcohol | |||||

| Heavy | 126 (73.7) | 38 (79.2) | 88 (71.5) | 0.34a | 0.361 |

| Hemoglobin pre | |||||

| <12.4g/dL | 65 (39.6) | 22 (48.9) | 43 (36.1) | 0.15a | 0.665 |

| Albumin pre | |||||

| <37.0g/L | 30 (34.1) | 7 (25) | 23 (38.3) | 0.24a | 0.07 |

| Co morbidities | |||||

| DM | 25 (14.6) | 8 (16.7) | 17 (13.8) | 0.63a | 0.72 |

| COPD | 18 (10.5) | 3 (6.2) | 15 (12.2) | 0.4a | |

| Liver disease | 39 (22.8) | 11 (22.9) | 28 (22.8) | 1a | |

| Cardiopathy | 42 (24.6) | 11 (22.9) | 31 (25.2) | 0.85a | |

| N | |||||

| N0 | 83 (48.6) | 21 (43.8) | 62 (50.4) | 0.25b | 0.933 |

| N1 | 25 (14.6) | 8 (16.7) | 17 (13.8) | ||

| N2a+N2b+N2c | 58 (33.9) | 17 (9.94) | 41 (23.96) | ||

| N3 | 5 (2.9) | 2 (1.16) | 3 (1.74) | ||

| Location | |||||

| Larynx | 67 (39.2) | 18 (10.5) | 49 (28.6) | 0.86a | 0.539 |

| Pharyngolaryngeal | 104 (60.8) | 30 (62.5) | 74 (60.2) | ||

| Rt pre | |||||

| Yes | 12 (7.0) | 4 (8.3) | 8 (6.5) | 0.74a | |

| CRT pre | |||||

| Yes | 15 (8.8) | 9 (18.8) | 6 (4.9) | 0.01a | 0.120 |

| Tracheotomy pre | |||||

| Yes | 77 (45) | 28 (58.3) | 49 (39.8) | 0.04a | 0.144 |

Rt, radiotherapy; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; pre, preoperative; DM, diabetes mellitus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases.

It was found that ASA 2 and 3, prior CRT, tracheotomy performed before surgery, and low levels of hemoglobin were associated with fistula development in the univariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, only the ASA classification maintained statistical significance (p<0.05). Albumin, prior CRT, and tracheotomy performed before surgery showed predictive potential (p<0.2) for inclusion in the model.

Although albumin did not achieve statistical significance in the univariate analysis and there were many missing albumin values in this sample (85 missing), it was observed that its exclusion from the model substantially reduced the validity (particularly regarding sensitivity).

Alcohol consumption, preoperative hemoglobin<12.5g/dL, DM presence, N-classification, primary tumor location and extension, and no prior Rt were not associated with fistula development, but increased the CDR's prognostic accuracy (regarding the balance of sensitivity-specificity) and thus were also included.

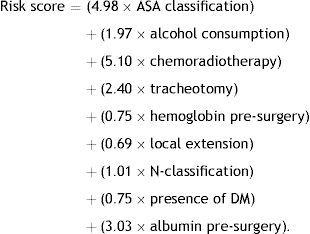

The model therefore included all pre-operative variables analyzed that presented a p-value<0.2 and all those considered important by a systematic review previously conducted by this team.4 The best results were obtained using the following model:

This model presented an AUC of 0.74 (95% CI 0.61–0.86), as shown in Fig. 1.

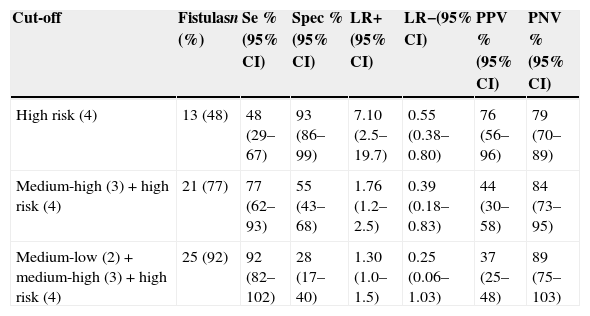

The model's score stratification into four different risk categories is proposed: low risk (for a score ≤9.88), medium-low (9.881–12.25), medium-high (12.26–17.1), and high risk (score >17.1). This stratification resulted in the prognostic accuracy values in Table 4. The values for the cut-offs were selected by an assessment of AUC coordinates, using those that provided best fit.

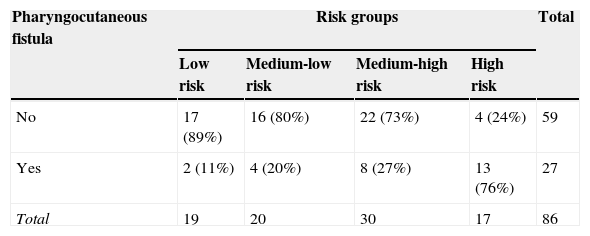

Approximately half of the participants (48%) who developed a pharyngocutaneous fistula were classified as high risk. By associating the three highest risk groups (high+medium-high+medium-low), 92% of fistula development was predicted. It was also observed that with an increase in the risk degree, more subjects develop fistula (p<0.001 for chi-squared in an association and trend analysis).

A high specificity for the high-risk group (93%) was noted, with moderately high positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of (7.10) and positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) with high results (76% and 79% respectively) (Table 5). With the three groups of medium-low/medium-high/high risk, a sensitivity of 92%, negative likelihood ratio (LR-) of 0.25, and NPV of 89% were obtained.

Risk stratification of modelCat2 and validity measures for the different cut-offs.

| Cut-off | Fistulasn (%) | Se %(95% CI) | Spec %(95% CI) | LR+(95% CI) | LR−(95% CI) | PPV %(95% CI) | PNV %(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High risk (4) | 13 (48) | 48 (29–67) | 93 (86–99) | 7.10 (2.5–19.7) | 0.55 (0.38–0.80) | 76 (56–96) | 79 (70–89) |

| Medium-high (3)+high risk (4) | 21 (77) | 77 (62–93) | 55 (43–68) | 1.76 (1.2–2.5) | 0.39 (0.18–0.83) | 44 (30–58) | 84 (73–95) |

| Medium-low (2)+medium-high (3)+high risk (4) | 25 (92) | 92 (82–102) | 28 (17–40) | 1.30 (1.0–1.5) | 0.25 (0.06–1.03) | 37 (25–48) | 89 (75–103) |

Se, sensibility; Spec, specificity; LR+, positive likelihood; LR−, negative likelihood; PPV, positive predictive value; PNV, negative predictive value; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

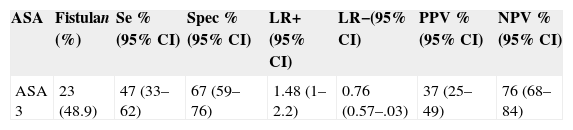

The measures of prognostic validity for ASA classification were also calculated, in order to compare with the results of Farwell et al.8; these values are shown in Table 6. Thus, this derived model is statistically superior to ASA classification when compared the measures of prognostic validity.

Risk stratification of the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification and precision measurements.

| ASA | Fistulan (%) | Se %(95% CI) | Spec %(95% CI) | LR+(95% CI) | LR−(95% CI) | PPV %(95% CI) | NPV %(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA 3 | 23 (48.9) | 47 (33–62) | 67 (59–76) | 1.48 (1–2.2) | 0.76 (0.57–.03) | 37 (25–49) | 76 (68–84) |

Se, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; LR+, positive likelihood; LR−, negative likelihood; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Clinical decision rules (CDR) are instruments used to increase health professionals’ accuracy in diagnostic and prognostic assessment by summarizing the probability of a particular outcome.

Pharyngocutaneous fistula represents a major postoperative complication of laryngectomized patients. Until now, no CDR has been derived for determining the risk of fistula development; consequently, this study was conducted. As 13 variables were included, the inclusion of 130 to 195 participants was required. The present study included 171 patients, which should be an adequate number.5 It was decided to use four categories in order to maintain equilibrium between the best fit of the model and clinical application; i.e., on one hand, with a higher number of categories, the classification can be adjusted more effectively to the original score's AUC; on the other hand, clinical applicability improves with a lower number of categories.

In this analysis, the incidence of the pharyngocutaneous fistula was 28.1%, which is between the values obtained by other authors.9–14

For most authors, the male gender was more represented (in the present sample, 97.1%), and fistula developed around the 10th to the 15th postoperative day, as demonstrated in 38% of the present cases.1,15–23

This analysis has shown, in agreement with other studies,17,24,25 that for the advanced stage (IVa and IVb) there seems to be a higher fistula incidence. This relationship was not statistically significant both in the present as well as in other studies.1,10–13,15,16,18–23,26–29

The univariate analysis confirmed that CRT and prior tracheotomy are factors associated with formation of pharyngocutaneous fistula, as did other authors.9,12,13,24,26,30,31 Tracheotomy previous to the operation was not considered a risk factor for the fistulization by several authors15,18,20–22,25–28,31 contrary to the present findings. In performing the multivariate analysis, these variables remained as potential predictive factors for the fistula development, as other authors have concluded.24,30

In the univariate analysis, radiotherapy prior to surgery was not significant for pharyngocutaneous fistula development, as other authors concluded.2,11,14,18,20,21,25–29,32,33 Their inclusion in the final model did not add significant changes in accuracy, thus they were excluded.

ASA classification, unlike other studies,8,21,34 was significant as a risk factor for fistula development in the univariate and multivariate analysis, which demonstrates that the presence of pre-operative co-morbidities and functional status of the patient have a major importance in the development of intra- and post-surgical complications.

Few authors have assessed the ASA classification's predictive value8 for this outcome, although its relevance has been demonstrated in the present sample, reflecting the key role of the pre-operative control of comorbidities. Paradoxically, evaluating each comorbidity separately (DM, COPD, liver disease, and heart disease), they did not demonstrate significant association with fistula development (both in the univariate and multivariate analysis). In this aspect, the available evidence is contradictory, as some authors reported the same results11,13 while others found a significant relationship between fistula and these comorbidities.1,12,15,16,20,21,34

After the multivariate analysis, pre-operative hypoalbumin (<3.7g/L) was an independent factor for the development of the pharyngocutaneous fistula, as other authors concluded.12,15,20,34

In the available literature, it was not possible to find a CDR developed specifically for stratifying patients by their risk of pharyngocutaneous fistula formation after pharyngolaryngectomy and total laryngectomy.

For the high-risk group, a high specificity was observed, and therefore the ability to determine among patients at highest risk those who will not develop pharyngocutaneous fistula. However, the model identified with high sensitivity the groups of medium-low+medium-high+highrisk subjects who will develop a fistula. In a hospital setting, this allows the distribution of economic and personnel resources primarily to patients with higher probability for the occurrence of postoperative complications. It also allows healthcare professionals to act more intensively and earlier in the pre-operative and post-operative period in order to assist the identified the risk group.

The terrible consequences for the patient's quality of life and prognosis after development of pharyngocutaneous fistula are well-known. Moreover, the economic resources targeted to the healing this complication are a tremendous financial burden on any healthcare system.

It should be emphasized that the derived model has some limitations. The collection of the variables was performed retrospectively and therefore was not as complete and accurate as it would have been with a prospective basis. Examples include the absence of albumin in the preoperative records of 85 patients and the lack of observed records to characterize the nutritional status of the patient prior to surgery. Regardless of the limiting factors, a CDR has been developed for easy application with robust values for prognostic accuracy, namely the AUC value of 0.76 (95% CI 0.64–0.87).

Final considerationsWe have statistically calculated a mathematical model with a good accuracy to detect the groups with medium/high risk of pharyngocutaneous fistula development. Ulteriorly, it will allow a best distribution of economic and personal resources targeting to patients with higher probability of this complication occurrence. These study’ major strengths are the fact that it represents first adequate and specifically CDR derived for the pharyngocutaneous fistula development risk stratification that additionally presented robust values of prognostic validity. The major limitations of the study are its retrospective and unicenter design and a modest sample size. Despite these limitations our CDR outperformed the ASA classification – which was validated for this outcome prediction.

This CDR is presented as a proposal for a later prospective multicenter validation, reliability assessment and optimization. We also wish to assess their applicability practice among health professionals and therefore make an economic impact and ease of use analysis of implementation among health services in our country.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the staff of the hospital that helped in the execution of this study. This work was a part of a Master's Thesis in Evidence-based Medicine from the University of Medicine of Porto.

Please cite this article as: Cecatto SB, Monteiro-Soares M, Henriques T, Monteiro E, Moura CIFP. Derivation of a clinical decision rule for predictive factors for the development of pharyngocutaneous fistula postlaryngectomy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:394–401.

Institution: Work conducted at the Portuguese Institute of Oncology, city of Oporto (IPOPFG-EPE, Oporto), Department of Otolaryngology, under the sphere of the Master's Degree Program in Evidence and Decision Making in Healthcare – part of a Master's thesis defended by the main author in November 2012 at Medicine School, University of Oporto – Portugal.