Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity present deficits in their cellular immunity that contribute to neoplastic growth. Thus, the inflammatory activity, such as the immunological response to the tumor, can be used as a prognostic factor.

ObjectivesTo evaluate the correlation between peritumoral inflammation and clinical characteristics of the patients, survival, and the disease-free interval.

MethodsThe study sample consisted of a retrospective hospital-based cohort of patients undergoing surgery for resection of oral cavity tumor. The inflammatory infiltrate on the slides was evaluated semi-quantitatively, and were divided into minor and major inflammatory processes.

ResultsThis study included 57 tumor samples, with infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. The log-rank test showed no significance for the survival curves and recurrence of the “minor inflammatory” and “major inflammatory” processes, with p=0.14 and p=0.24, respectively. A direct association between age and inflammation (p=0.04) was observed, as well as an indirect association between the degree of tumor differentiation and inflammation (p=0.01).

ConclusionAlthough associated with histological differentiation, the peritumoral inflammatory process cannot be considered a prognostic factor in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, as it is not related to survival and disease-free interval.

Pacientes com carcinoma epidermoide de cavidade oral mostram déficits em sua imunidade celular, que contribuem para o crescimento neoplásico. Assim, a atividade inflamatória, como resposta imunológica ao tumor, pode servir como fator prognóstico.

ObjetivosAvaliar a correlação entre o processo inflamatório peritumoral com as características clínicas dos pacientes, com a sobrevida e com o tempo livre de doença.

MétodoA amostra deste estudo foi composta por uma coorte retrospectiva de base hospitalar com pacientes submetidos à cirurgia para remoção de carcinoma epidermoide de cavidade oral. O infiltrado inflamatório presente nas lâminas foi avaliado semi quantitativamente, sendo dividido em processo inflamatório: menor e maior.

ResultadosAnalisaram-se 57 amostras tumorais, com infiltrado de linfócitos, plasmócitos e histiócitos. O teste log-rank não mostrou significância para as curvas de sobrevida e de recidiva dos processos “inflamatório menor” e “inflamatório maior”, p=0,14 e p=0,24, respectivamente. Observou-se associação direta da idade com o processo inflamatório (p=0,04), e relação indireta entre o grau de diferenciação tumoral e o processo inflamatório (p=0,01).

ConclusãoO processo inflamatório peritumoral, embora relacionado com a diferenciação histológica, não pode ser considerado fator prognóstico de carcinoma epidermoide de cavidade oral, pois não se relaciona com sobrevida e tempo livre da doença.

Despite treatment advances over the last 20 years, squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity (SCCOC) continues to have survival rates at five years of 45–50%,1–3 mainly due to its heterogeneous behavior.4 This fact has led to several studies aiming to detect biological and molecular characteristics that may indicate prognosis and treatment of these tumors; most of them relate to histopathological staging of the surgical specimen and do not have direct impact on clinical practice.5 Currently, it is also known that the presence of neck metastasis and surgical margin involvement are prognostic factors for SCCOC.6,7

Innate immunity is the first reaction of the host to an offending agent. Adaptive immunity is a delayed type of immunity that leaves immunological memory, with the participation of B lymphocytes (humoral immunity) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (cellular immunity). According to Abbas et al.8 the main anti-tumor defense mechanism is the death of neoplastic cells by CD8+ T or cytotoxic T lymphocytes. However, individuals with SCCOC have cellular immunity deficits, including alterations in monocyte chemotaxis and defects in the interaction between the monocytes that have antigens and lymphocytes. These defects contribute to neoplastic growth. According to Whiteside9 the same mechanisms used for immunological escape in human malignancies may explain discrepancies between failures and successes in immunotherapy.

Inflammatory activity, such as immunological response to the tumor, could be used as a prognostic factor, since the lower the inflammatory infiltrate, the greater the risk of regional or distant metastasis.10–12 However, Vieira et al.7 observed a correlation between a higher degree of malignancy and higher inflammatory intensity, suggesting a positive association between the intensity of the inflammatory response and the degree of tumor differentiation, without necessarily influencing patient prognosis.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the correlation between the peritumoral inflammatory process and clinical characteristics of patients with SCCOC, as well as survival and disease-free interval.

MethodsThe study sample consisted of a retrospective hospital-based cohort of patients undergoing surgery from March of 2003 to June of 2010 for resection of SCCOC, of which surgical specimens were part. Data related to the independent variables that could be associated to the survival of cancer patients, such as sociodemographic variables (gender, age, smoking status, and alcohol consumption), clinical variables (primary subsite), clinical staging (TNM, clinical stage), and histological staging (differentiation, angiolymphatic invasion, and perineural invasion) were obtained through medical file review.

Excluded were patients who did not have tumor tissue samples stored, as well as those with a surgical margin compromised by the tumor at the histopathological analysis of surgical specimens, patients lost to post-surgical follow-up, and those who died from causes unrelated to the disease. All studied subjects, at the time of the surgery, signed the informed consent form approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC No. 9371/2003).

Histological analysisHistopathological assessment of the cases was conducted at the Department of Pathology, after the paraffin blocks were removed from the Head and Neck Surgery Surgical Specimen Bank (CEP No. 9371/2003). These blocks were processed to obtain four-micrometer sections and routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological analysis.

The peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate was characterized by the influx of mononuclear cells from the chronic inflammatory process (lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and histiocytes) into the connective tissue that permeates the invading neoplastic cells that have broken the basal membrane of the squamous epithelial oral mucosa. This infiltrate was stained with hematoxylin-eosin and the 4 micron-thick tumor histological sections were assessed by two experienced examiners using the semiquantitative method by light microscopy with objective lens, with a 40× magnification. The inflammatory infiltrate was quantified as:

- –

Grade 0: when no or only rare mononuclear inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and/or histiocytes) were identified in the interface between the invasive tumor and chorion;

- –

Grade 1 (mild): when less than 50% of the interface between the invasive tumor and chorion was infiltrated by mononuclear inflammatory cells;

- –

Grade 2 (moderate): when the inflammatory infiltrate was ≥50% and ≤75% in the tumor-chorion interface;

- –

Grade 3 (intense): when the inflammatory response was present in >75% of the tumor-chorion interface.

For the statistical analysis, patients with inflammatory process grade zero and one (0 and 1) were grouped as minor inflammatory process and those classified as grades 2 and 3, as major inflammatory process. Two response variables were considered separately: death and recurrence. For each one, the association with the inflammatory process (explanatory variable) was assessed.

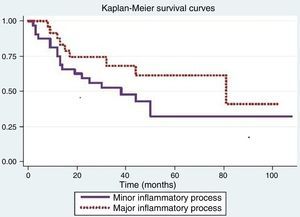

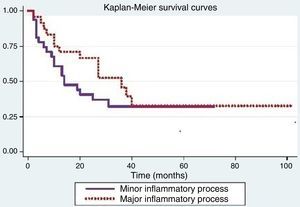

Survival curves for each variable were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, which were compared using the log-rank test. Cox regression (proportional hazards model) was used to evaluate the effect of the inflammatory process on response (death or recurrence), considering the adjustment for each of the other variables.13

The association of the inflammatory process with the other sociodemographic aspects, clinical aspects, clinical staging, and histological staging variables were evaluated by Fisher's exact test.

ResultsA total of 57 tumor samples were analyzed, in which the peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate consisted of lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and/or histiocytes.

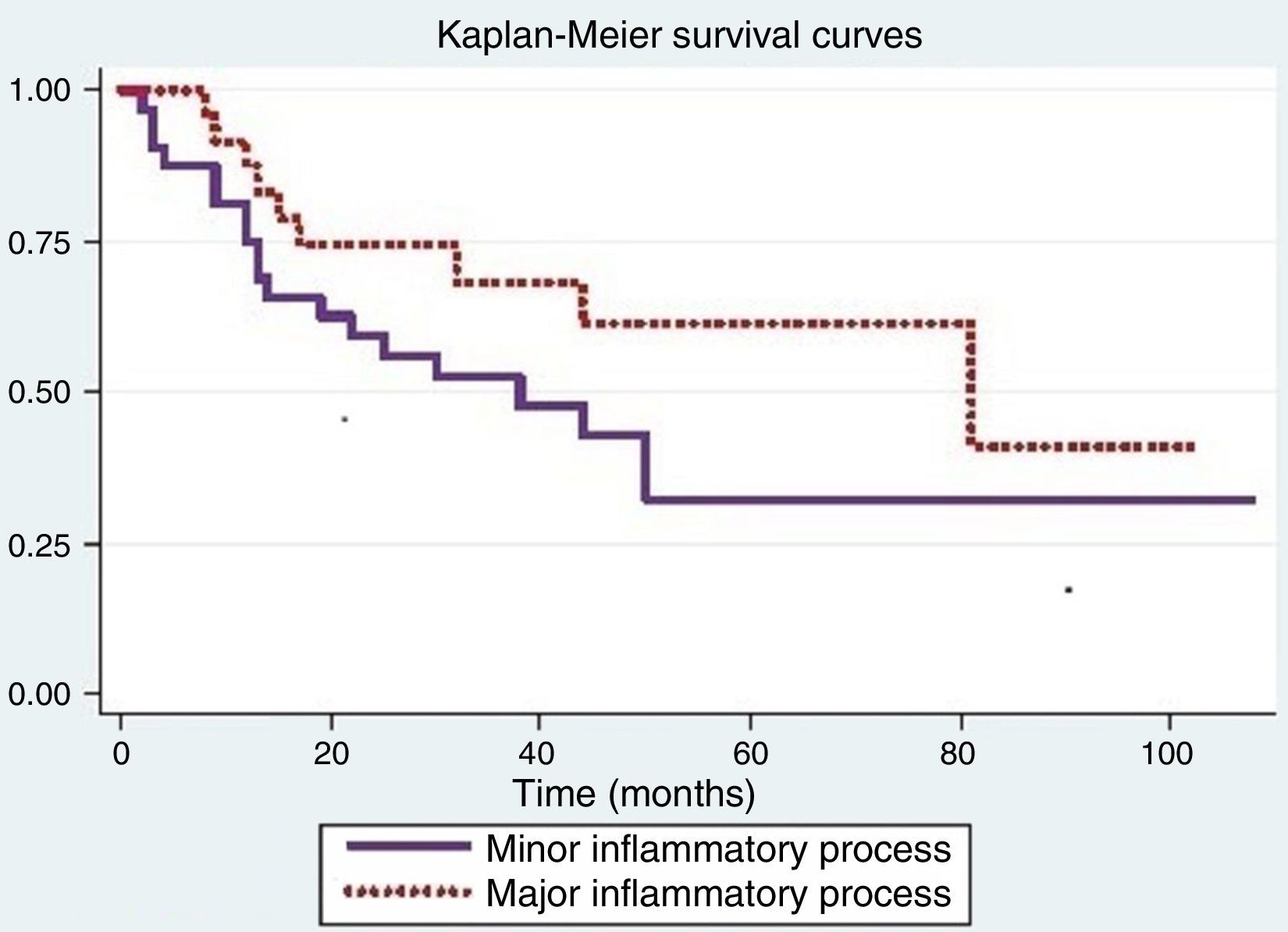

Fig. 1 shows that the probability of survival in over 12 months was 0.75 (95% CI: 0.56–0.87) for individuals with minor inflammatory process (Grades 0 and 1) and 0.88 (95% CI>0.66–0.96) for subjects with major inflammatory process (Grades 2 and 3). The log-rank test used to compare survival curves of both processes showed no significance (p=0.14).

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess differences between inflammatory processes when adjusted for variables that were significant in the log-rank test. When adjusted for smoking, there was a difference in inflammatory response (p=0.05); for the other variables, the results were not significant.

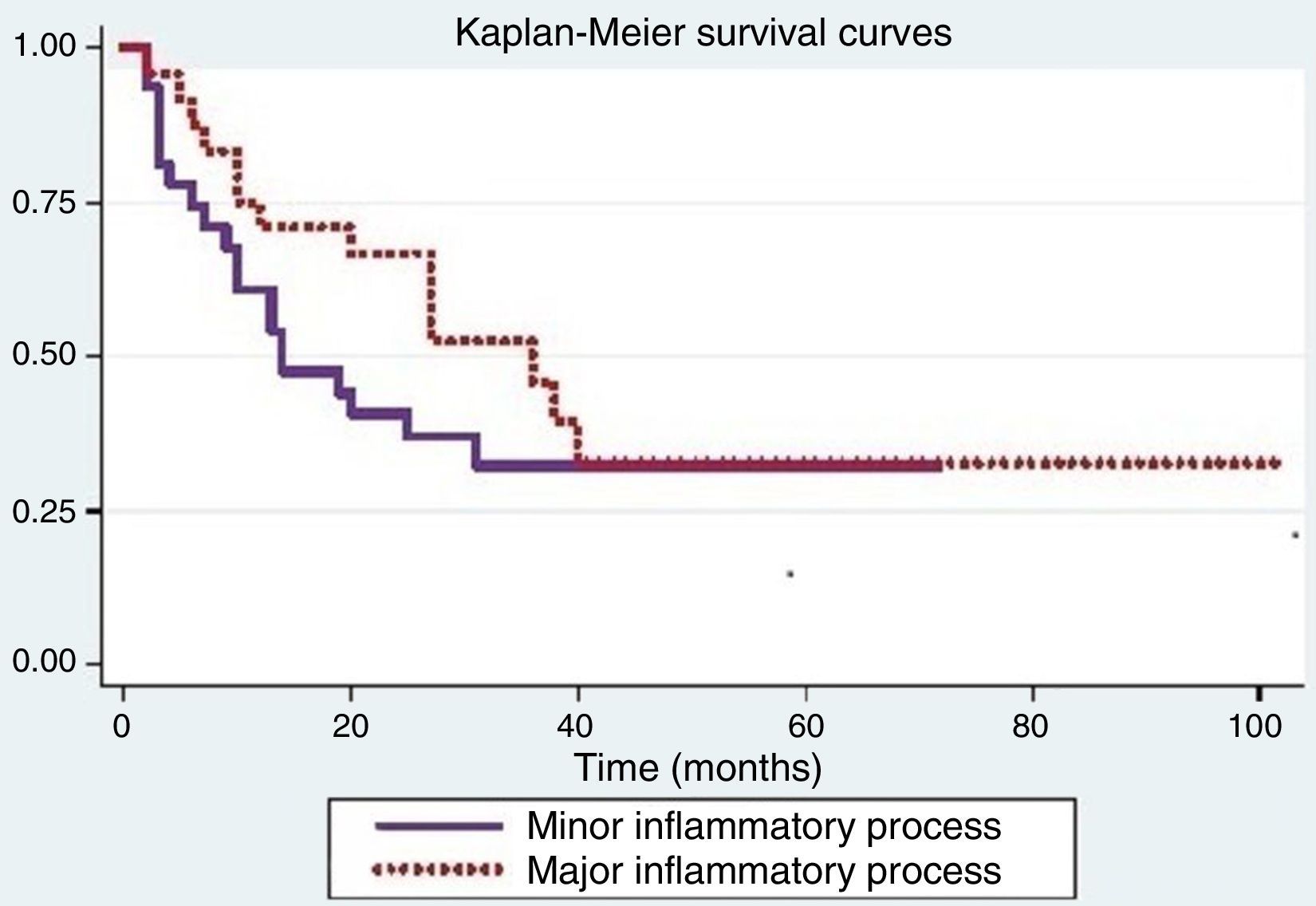

Tumor recurrence is shown in Fig. 2. The log-rank test used to compare the recurrence curves for both processes was not significant (p=0.24).

Positive significance for recurrence was observed when considering age (p=0.04), smoking (p<0.01), alcoholism (p<0.01), and degree of tumor differentiation (p=0.02). The other variables were not significant.

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the differences between inflammatory processes when adjusted for variables that were significant in the log-rank test. When adjusting for smoking, a difference was observed between the inflammatory processes (p=0.05).

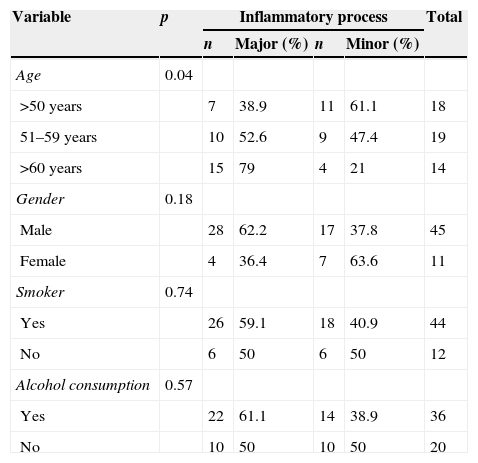

The association of the inflammatory process with the other variables can be observed in Tables 1 and 2. There is a direct association between age and the inflammatory process (p=0.04), as major inflammatory processes were associated with older ages and minor inflammatory processes with younger ages (Table 1).

Frequency distribution of the inflammatory process in relation to sociodemographic variables and Fisher's exact test p-value.

| Variable | p | Inflammatory process | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Major (%) | n | Minor (%) | |||

| Age | 0.04 | |||||

| >50 years | 7 | 38.9 | 11 | 61.1 | 18 | |

| 51–59 years | 10 | 52.6 | 9 | 47.4 | 19 | |

| >60 years | 15 | 79 | 4 | 21 | 14 | |

| Gender | 0.18 | |||||

| Male | 28 | 62.2 | 17 | 37.8 | 45 | |

| Female | 4 | 36.4 | 7 | 63.6 | 11 | |

| Smoker | 0.74 | |||||

| Yes | 26 | 59.1 | 18 | 40.9 | 44 | |

| No | 6 | 50 | 6 | 50 | 12 | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.57 | |||||

| Yes | 22 | 61.1 | 14 | 38.9 | 36 | |

| No | 10 | 50 | 10 | 50 | 20 | |

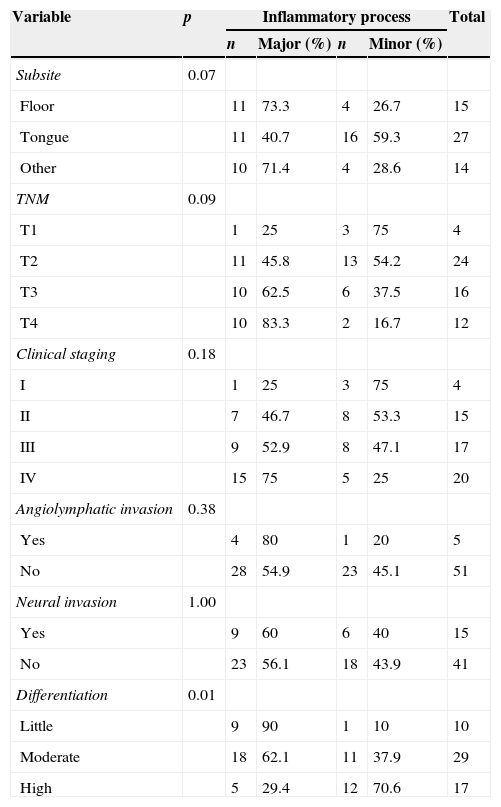

Frequency distribution of the inflammatory process in relation to age and differentiation and Fisher's exact test p-value.

| Variable | p | Inflammatory process | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Major (%) | n | Minor (%) | |||

| Subsite | 0.07 | |||||

| Floor | 11 | 73.3 | 4 | 26.7 | 15 | |

| Tongue | 11 | 40.7 | 16 | 59.3 | 27 | |

| Other | 10 | 71.4 | 4 | 28.6 | 14 | |

| TNM | 0.09 | |||||

| T1 | 1 | 25 | 3 | 75 | 4 | |

| T2 | 11 | 45.8 | 13 | 54.2 | 24 | |

| T3 | 10 | 62.5 | 6 | 37.5 | 16 | |

| T4 | 10 | 83.3 | 2 | 16.7 | 12 | |

| Clinical staging | 0.18 | |||||

| I | 1 | 25 | 3 | 75 | 4 | |

| II | 7 | 46.7 | 8 | 53.3 | 15 | |

| III | 9 | 52.9 | 8 | 47.1 | 17 | |

| IV | 15 | 75 | 5 | 25 | 20 | |

| Angiolymphatic invasion | 0.38 | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 80 | 1 | 20 | 5 | |

| No | 28 | 54.9 | 23 | 45.1 | 51 | |

| Neural invasion | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 60 | 6 | 40 | 15 | |

| No | 23 | 56.1 | 18 | 43.9 | 41 | |

| Differentiation | 0.01 | |||||

| Little | 9 | 90 | 1 | 10 | 10 | |

| Moderate | 18 | 62.1 | 11 | 37.9 | 29 | |

| High | 5 | 29.4 | 12 | 70.6 | 17 | |

According to Roithmaier et al.14 the immune system has an important role in the development of malignancies, since patients undergoing immunosuppression to receive organ transplants were 21 times more likely to have head and neck neoplasms than the overall population. Moreover, Galon et al.15 verified that the immune system also influences cancer recurrence, as in colon cancer, and the presence of T cells in the resected tumor predicts tumor evolution more accurately than staging. However, the role of the immune system in cancer progression is not clear. The immune surveillance concept states that the system should recognize and destroy the transformed cell clones before they generate tumors. However, the importance of such surveillance has been met with reservation, since they do not appear to react to many neoplasms.8 Conti-Freitas et al.16 when analyzing cell cultures in 17 patients with laryngeal cancer, concluded that there was a deficiency of the immunological system (decreased induced lymphoproliferation in stimulated cultures and deficiencies in the production of IFN-y and TNF-α in unstimulated cultures) that tends to normalize after tumor resection (laryngectomy) or BCG use.

According to Whiteside9 there are several possible mechanisms for tumors to escape immunologic suppression including: the expression of poorly immunogenic antigens, defects in antigen processing pathways, inadequate interactions, and production of immunosuppressive factors by inflammatory cells adjacent to the neoplasm. We believe that is was what happened in our study, since no statistically significant differences were observed comparing the prognostic factors survival and disease-free interval, with the presence of minor and the major inflammatory processes. This result may be due to sample size (57 tumors), as Manzano et al.11 with a sample of 46 patients with SCCOC, also found no significant difference between the intensities of peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate and survival curves, although they observed that the more frequent the presence of neck metastasis, the lower the intensity of the infiltrate.

In this study, we observed a statistically significant difference between the degree of tumor differentiation and peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate; the lower the tumor differentiation (more aggressive), the greater the inflammatory process.

In a similar study, Vieira et al.7 concluded that the cellular immune response is a major defense mechanism of the oral mucosa, as they observed the expression of a greater number of T lymphocytes in undifferentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Moreover, Manzano et al.11 showed a strong tendency toward a worse prognosis among tumors with poorly differentiated cells and less inflammatory infiltrate.

The results of the present study show that, as tumor stage increases, such as in growth (TNM classification), there is a trend toward increased peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate, but without statistical differences, which means that the inflammatory infiltrate tends to increase along with the tumor mass growth. This observation leads to the conclusion, as Chaves et al.17 that the imbalance in the immune system does not necessarily correlate with the number of defense cells that are present, but often results from failure in the function, regulation, or migration, of a population of immune cells to the tumor site. Similarly, Abreu et al.18 observed an inverse association between advanced tumors and degree of differentiation, and Costa et al.19 demonstrated worse prognosis in advanced tumors, considering metastasis as the main prognostic indicator.

It has been mentioned that the intensity of the inflammatory infiltrate ranges from mild to severe in tumors; the highest density of inflammatory cells is associated with lower rates of recurrence and, when lymphocytes penetrate the tumor, prognosis is more favorable.15 However, this study only showed that older patients had a higher incidence of inflammatory process, which was statistically significant; however, this increased cell density did not translate into increased survival. It is believed that all tested cell lines are present, but only T helper lymphocytes are associated with the degree of tumor malignancy and not to the amount of inflammatory cells. Conversely, Chaves et al.17 when studying 30 cases of SCCOC, found no statistical correlation between inflammatory infiltrate and age.

It was also possible to verify that survival and recurrence showed an association with smoking, alcohol consumption and degree of tumor differentiation, similar to that obtained by Montoro et al.6 who observed a statistical significance between survival and the following variables: age, gender, smoking and alcohol consumption, while Almeida et al.20 showed an association between smoking and alcohol consumption with prognosis, in contrast to Oliveira et al.21 who found no influence of smoking on recurrences and metastases.

Further studies must be conducted with a larger sample size to verify the real influence of the inflammatory process as a prognostic factor and other possible interactions with oral cancer.

ConclusionThe peritumoral inflammatory process, although associated with the degree of histological differentiation, cannot be considered a prognostic factor for SCCOC, as it is not associated with survival and disease-free interval. Additionally, there was a direct association between the peritumoral inflammatory process and factors such as age, smoking, and alcohol consumption.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Affonso VR, Montoro JRMC, de Freitas LCC, Saggioro FP, de Souza L, Mamede RCM. Peritumoral infiltrate in the prognosis of epidermoid carcinoma of the oral cavity. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:416–21.

Institution: Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRB-USP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.