Early diagnosis of hearing loss minimizes its impact on child development. We studied factors that influence the effectiveness of screening programs.

ObjectiveTo investigate the relationship between gender, weight at birth, gestational age, risk factors for hearing loss, venue for newborn hearing screening and “pass” and “fail” results in the retest.

MethodsProspective cohort study was carried out in a tertiary referral hospital. The screening was performed in 565 newborns through transient evoked otoacoustic emissions in three admission units before hospital discharge and retest in the outpatient clinic. Gender, weight at birth, gestational age, presence of risk indicators for hearing loss and venue for newborn hearing screening were considered.

ResultsFull-term infants comprised 86% of the cases, preterm 14%, and risk factors for hearing loss were identified in 11%. Considering the 165 newborns retested, only the venue for screening, Intermediate Care Unit, was related to “fail” result in the retest.

ConclusionsGender, weight at birth, gestational age and presence of risk factors for hearing loss were not related to “pass” and/or “fail” results in the retest. The screening performed in intermediate care units increases the chance of continued “fail” result in the Transient Otoacoustic Evoked Emissions test.

O diagnóstico precoce da surdez minimiza impactos no desenvolvimento infantil. Fatores que interferem na efetividade dos programas de triagem são estudados.

ObjetivoVerificar a relação entre sexo, peso ao nascimento, idade gestacional, presença de risco par deficiência auditiva, local de realização da triagem auditiva neonatal e resultados “passa” e “falha” no reteste.

MétodoEstudo de coorte prospectiva, em hospital de referência terciário. A triagem foi realizada em 565 neonatos, por meio das emissões otoacústicas evocadas transientes, em três unidades de internação antes da alta hospitalar e o reteste, no ambulatório. Sexo, peso ao nascimento, idade gestacional, presença de indicadores de risco para deficiência auditiva e local de realização do exame foram considerados.

ResultadosNasceram a termo 86%, prematuros 14% e risco para deficiência auditiva, 11%. Dentre os 165 neonatos retestados, apenas o local de realização do exame, Unidade de Cuidados Intermediários, se relacionou com manutenção da “falha” no reteste.

ConclusõesSexo, peso ao nascimento, idade gestacional e presença de indicadores de risco para deficiência auditiva não se relacionaram com “passar” e/ou “falhar” no reteste. A realização do exame em unidades de cuidados intermediários aumenta a chance de permanência de “falha” no exame de Emissões Otoacústicas Evocadas Transientes.

With the use of electrophysiological and electroacoustic tests in children, the early diagnosis for hearing loss became a possibility in the first months of life, through the universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS).1 In Brazil, UNHS became mandatory for all newborns by Federal Law No. 12,303.

Several factors are important for a good understanding and effectiveness of UNHS testing; these include test site, clinical conditions of the newborn, and performing the test prior to hospital discharge. In addition, in at least 90% of those who fail the first UNHS exam, a retest should be performed, either before hospital discharge, or by the third month of life.2

Inability to achieve this recommended standard can occur for reasons inherent to neonates, such as death, postnatal illness and hospitalization in another unit, or by lack of family compliance. Thus, the challenge of reducing the number of failures in the initial examination and also the challenge of avoiding non-attendance of these children for retest are still good reasons for studying this topic.3–5 The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between gender, birth weight, gestational age, presence of risk factors for hearing loss, site where UNHS is carried out, and “pass” and “fail” results in the retest.

MethodsThe study was conducted in a tertiary referral hospital, with local Ethics Committee approval (Process No. 3395/09), from September 2011 to June 2012. The Free and Informed Consent Form was signed by the parent or legal guardian of the newborn.

This was a prospective cohort study.

During the study period, 565 neonates underwent UNHS in three different units of hospitalization: neonatal rooming-in (NRI), special care unit (ECU) and intermediate care unit (ICU), before hospital discharge. For babies with an abnormal initial examination, retesting was performed in an outpatient speech therapy clinic after hospital discharge. Hearing screening was performed by means of transient evoked otoacoustic emissions, using portable equipment (OtoRead/Interacoustics), with the newborn in a state of natural sleep in its mother's lap, or in the cradle.

The parameter PASS/FAIL described in the equipment protocol was used as analysis criterion, using clicks as stimuli at an intensity of 83dB SPL; six frequency bands (1500–4000Hz) were evaluated. The values considered as “PASS” were otoacoustic emissions present in a signal/noise ratio of 6dB in at least three consecutive frequency bands, including 4000Hz, and a maximum time of 64s to perform the test.

The variables of gender, birth weight, gestational age, presence of risk factors for hearing loss2 and test site (NRI, ECU and ICU) were considered in the statistical analysis of neonates with “failure” in their initial evaluation. Chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests were used.Analyses were considered significant if p≤0.05. In the statistical analysis, SPSS software version 21.0 was used.

ResultsBefore hospital discharge, 565 neonates underwent UNHS; 48% (n=270) were female and 52% (n=295) were male. The average birth weight was 3663g (minimum of 695g and maximum of 4700g). Regarding gestational age, 86% (n=484) were born at term, and 14% (n=81) were premature.

Risk factors for hearing loss were present in 11% (n=65) of the neonates. A low Apgar score at birth (n=24), birth weight <1500g (n=11), ICU > 48h (n=10), mechanical ventilation in excess of five days (n=6), congenital syphilis (n=6), use of ototoxic drugs (n=4), child of drug-user mother (n=3), craniofacial malformation (n=2), congenital toxoplasmosis (n=1) and family history of hearing loss in children (n=1) were the risk factors.

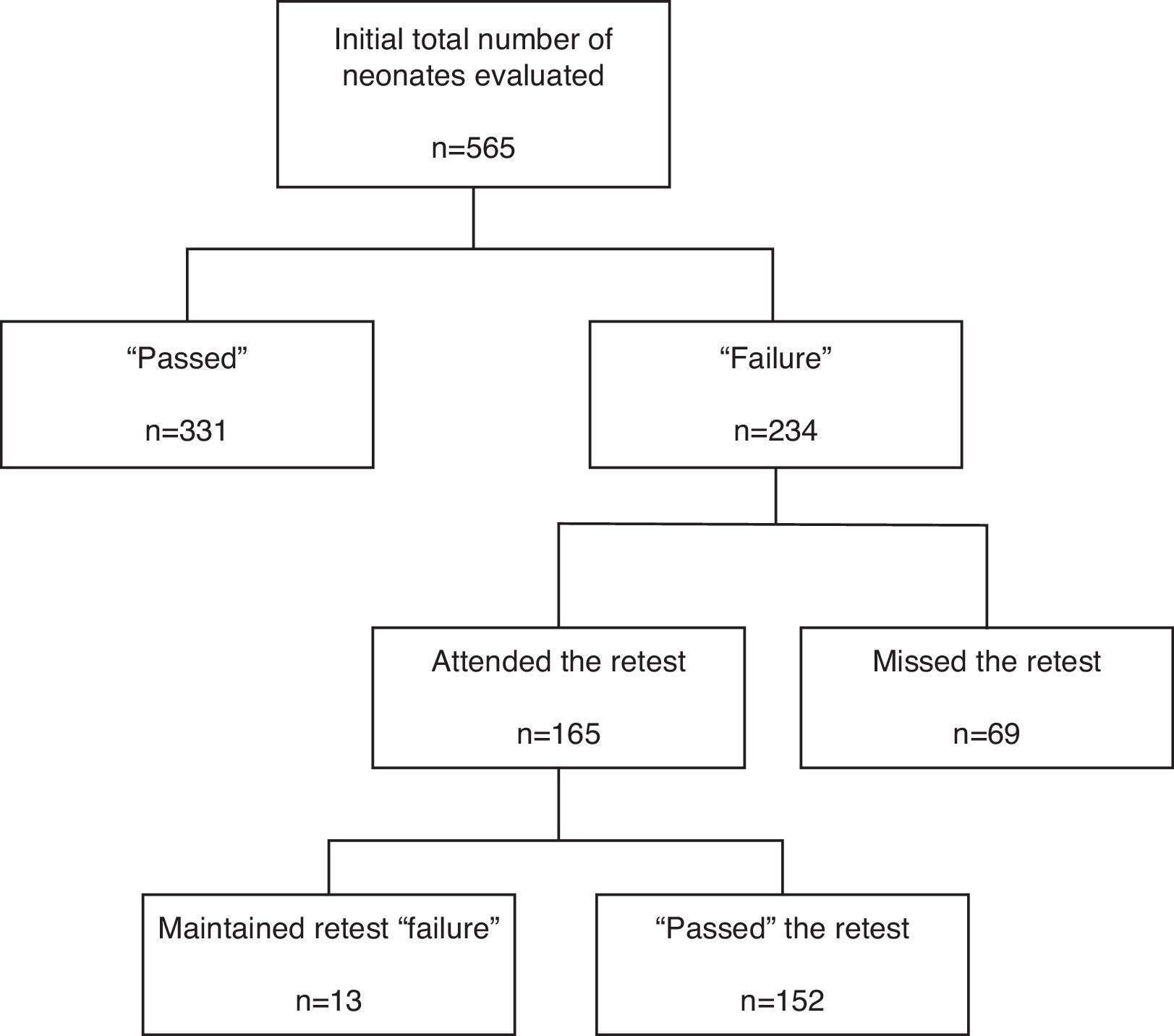

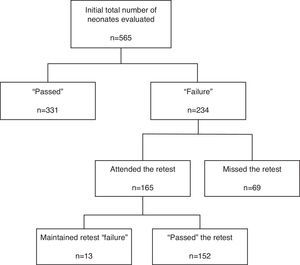

As shown in the flowchart of Fig. 1, 59% of neonates (n=331) “passed” in the initial evaluation. Among the 234 neonates who “failed”, 30% (n=69) did not attend the retest, resulting in reassessment of 165 neonates, only 8% of whom (n=13) confirmed the initial “failure”.

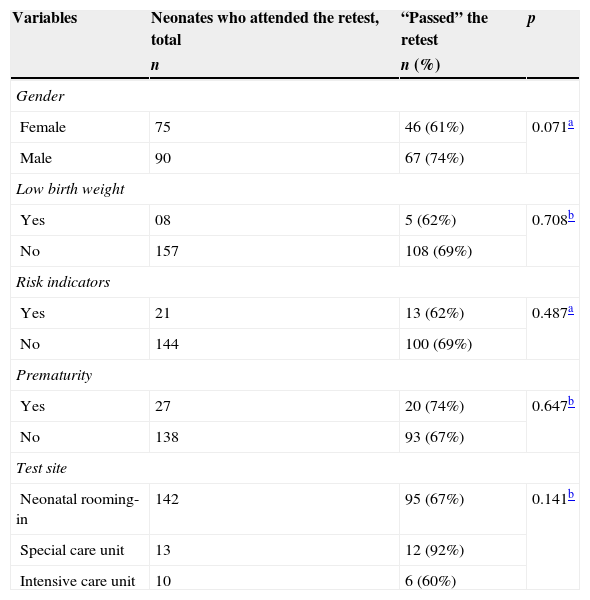

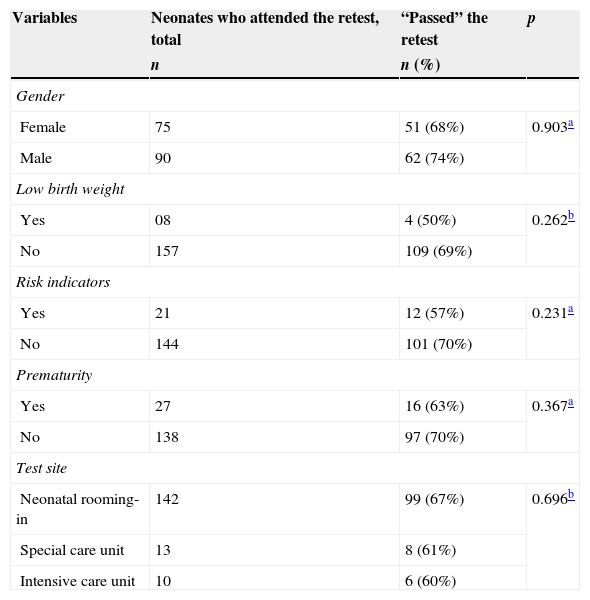

The relationship among the variables gender, prematurity, presence of risk factors for hearing loss, exam site, and a “pass” on the retest was not statistically significant in both ears (Tables 1 and 2).

Relationship between “to pass” the retest on the right ear and the following variables: gender, low birth weight, risk factors, prematurity and test site.

| Variables | Neonates who attended the retest, total | “Passed” the retest | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 75 | 46 (61%) | 0.071a |

| Male | 90 | 67 (74%) | |

| Low birth weight | |||

| Yes | 08 | 5 (62%) | 0.708b |

| No | 157 | 108 (69%) | |

| Risk indicators | |||

| Yes | 21 | 13 (62%) | 0.487a |

| No | 144 | 100 (69%) | |

| Prematurity | |||

| Yes | 27 | 20 (74%) | 0.647b |

| No | 138 | 93 (67%) | |

| Test site | |||

| Neonatal rooming-in | 142 | 95 (67%) | 0.141b |

| Special care unit | 13 | 12 (92%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 10 | 6 (60%) | |

Relationship between “to pass” the retest on the left ear and the following variables: gender, low birth weight, risk factors, prematurity and test site.

| Variables | Neonates who attended the retest, total | “Passed” the retest | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 75 | 51 (68%) | 0.903a |

| Male | 90 | 62 (74%) | |

| Low birth weight | |||

| Yes | 08 | 4 (50%) | 0.262b |

| No | 157 | 109 (69%) | |

| Risk indicators | |||

| Yes | 21 | 12 (57%) | 0.231a |

| No | 144 | 101 (70%) | |

| Prematurity | |||

| Yes | 27 | 16 (63%) | 0.367a |

| No | 138 | 97 (70%) | |

| Test site | |||

| Neonatal rooming-in | 142 | 99 (67%) | 0.696b |

| Special care unit | 13 | 8 (61%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 10 | 6 (60%) | |

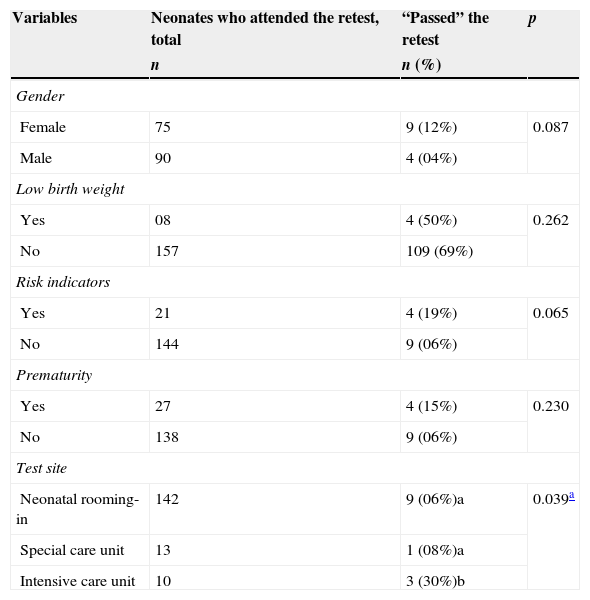

On the other hand, the ratio between these same variables and the persistence of “failure” on the retest in at least one ear was significant when the first examination was carried out at the intermediate care unit (Table 3).

Relationship between maintenance of retest “failure” in at least one ear and the following variables: gender, low birth weight, risk factors, prematurity and test site.

| Variables | Neonates who attended the retest, total | “Passed” the retest | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 75 | 9 (12%) | 0.087 |

| Male | 90 | 4 (04%) | |

| Low birth weight | |||

| Yes | 08 | 4 (50%) | 0.262 |

| No | 157 | 109 (69%) | |

| Risk indicators | |||

| Yes | 21 | 4 (19%) | 0.065 |

| No | 144 | 9 (06%) | |

| Prematurity | |||

| Yes | 27 | 4 (15%) | 0.230 |

| No | 138 | 9 (06%) | |

| Test site | |||

| Neonatal rooming-in | 142 | 9 (06%)a | 0.039a |

| Special care unit | 13 | 1 (08%)a | |

| Intensive care unit | 10 | 3 (30%)b | |

Hearing assessment in the first days of life that identifies hearing loss can result in a better prognosis for language development; the first months of life are considered a critical period of maturation and plasticity of the central auditory system.6,7

For an early identification of deafness, the use of objective measures such as recording evoked otoacoustic emissions and brainstem auditory evoked potential (BAEP) is recommended.2,7 However, on a large scale, Brazil utilizes evoked otoacoustic emissions as a first diagnostic step and, after a confirmed “failure” of this test, employs BAEP to substantiate the diagnosis.1,4

With confirmation of deafness, these children should be submitted to early intervention through individual hearing aid adaptation/cochlear implant, and speech therapy; these should be implemented by the sixth month of life.2 Therefore, hearing screening is recommended, preferably before hospital discharge.8–11

However, in the very first days of life before discharge from the hospital, there are some factors that can cause a UNHS test “failure” such as an elevated ambient noise level in inpatient units, the clinical conditions of the newborn, or the presence of vernix in the external auditory canal.4,12 But in the retest, when test conditions are better, it is possible to verify that the “failure” was due to a hearing problem, and not to unrelated factors.

Since ours is a teaching hospital with a large number of births per month, different inpatient units for the newborn were considered in this study. Our hospital has four inpatient units. NRI comprises healthy neonates, ECU houses neonates with any of the following factors: low birth weight (<2000g), gestational age less than 34 weeks, respiratory distress without immediate need for intubation and mechanical ventilation, or neonates whose mothers are unable to care for their children in the NRI, soon after birth. ICU receives newborns who need monitoring, but who do not require care in a neonatal intensive care unit (ICU), which is responsible only for severe cases.

This study shows that 92% of newborns “passed” the retest, an index very close to that recommended by JCIH,2 even though it occurred in a hospital that serves pregnant women and infants at high risk for hearing loss.

The loss of 30% in the population appropriate for retest can be explained in part by an increase of neonatal hearing screening programs in the cities of origin, that gives parents an option with easier access. Also, high-risk pregnancies increase the possibility of readmission of these neonates that would prevent their return. The lack of recognition, or even of understanding, of the importance of the hearing test is common and may also have an impact on the early identification of deafness.

Although the presence of risk factors for hearing loss and prematurity increases the chances of “failure” on UNHS,13,14 our study found no relationship between these factors and the persistence of “failure” on retest, but it did find a correlation with exam site, especially for those babies who underwent the initial examination in the ICU. This finding may be explained by the fact that neonates that remained in this unit are those presenting major complications before, during and/or after birth.

This study addressed the importance of completing the retest of otoacoustic emissions, but does not rule out a referral to BAEP, or even carrying out BAEP as a first step, especially in neonates at risk for hearing loss. However, the practice of conducting otoacoustic emission tests, mainly in the retest, reduced the number of false positives, especially when the initial assessment was conducted in in-hospital critical environments.

The children assessed in this study, after confirmation of retest “failure”, were referred for diagnostic evaluation; and, after confirmation of hearing loss, were referred for medical and audiologic treatment.

Even considering that the conditions for carrying out screening procedures before hospital discharge are not ideal, the retest is essential for an early identification of the baby's actual hearing impairment, emphasizing the importance of investing in factors that contribute to the adherence to retest, for example, education of those professionals involved in maternal and child health and in family counseling.

ConclusionGender, birth weight, gestational age and presence of risk factors for hearing loss were not related to “to pass” and/or “to fail” the retest. The examination carried out in intermediate care units increases the chances of permanence of “failure” in the transient evoked otoacoustic emission test.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: da Silva DPC, Lopez PS, Ribeiro GE, Luna MOM, Lyra JC, Montovani JC. The importance of retesting the hearing screening as an indicator of the real early hearing disorder. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:363–7.

Institution: Botucatu Medicine School, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Botucatu, SP, Brazil.